Jibanananda Das: Nationalism and Internationalism

Jibanananda Das had tried writing poetry in English, had written a few essays in the language too. But those did not go quite well and even when they did, it meant nothing for Bengali literature and its readers. He did not try being (in)famous the way Madhusudan Dutta did; Madhusudan Dutta had realized quite early on that it amounted to begging abroad. Having been a student of English literature and a teacher, Jibanananda had mastered the tongue of his Colonial overlords. His deep connections to English literature acted as a solid foundation for his later work in Bangla. It could be said that most of the authors who had helped Bengali literature to flourish in the beginning of the twentieth century were well acquainted with the English cannon.

Jibanananda Das, however, felt it was necessary to understand English in order to critique the poets and the literature. In his essay, “Desh, Kal O Kobita,” he had discussed this matter at length — that it was necessary to know English for the sake of Bengali poetry. But he did not believe that English poetry was the best of them all, of course. He thought that as it had spread in most parts of the world, and regardless of how it achieved it, it would act as a helpful vehicle, one that would help us become familiarized with the literature of the world in other languages. English, he thought, connected him to the greater world outside.

One must, however, keep the danger in mind in such a discussion regarding the poet. We cannot always talk of the life and work of great men without a little apprehension. Aside from the truth, there’s also a projection directed toward their lives, which is the only respite for the casual reader and the obsessive devotee. Buddhadeva Bose had from the very start stamped Jibanananda as a “poet of solitude,” and the label had stuck ever since with the Bengali reader, for it seems now that as a race we preferred the guides and their generalist, mediocre interpretation to the actual books themselves.

Of course, Buddhadeva Bose was an honest critic. He had done the brave thing of bringing Jibanananda Das close to the readers. Before Jibanananda’s Grey Manuscript had come out in 1936, Bose had written about the novelty in Jibanananda’s works in his journal Progoti. Jibanananda, however, had been neglected throughout much of the twentieth century, as evidenced by the 1972 Sahitya Academi’s list of notable Bengali poets, which included many later, relative nonentities, but left Das out. Even Rabindranath wasn’t unambiguous in his praise for the poet. He had remarked to him, a little annoyed, “No doubt you have the power of poetry in you, but why do you force yourself too much to the language?”

Yet it is the mark of a great poet to wrestle with the language and manage to tame it. Despite Tagore’s works being leading-edge for the most part, there was a conservatism apparent in him when it came to the use of language. His (in)famous argument with Nazrul is a case that reflected this. Though he had won the Nobel Prize for his own work, he couldn’t claim his Bengali as the language of all India. Jibanananda, on the other hand, had said, “The stage Bengali is right now, it is only natural for it to be the national language of India.”

Perhaps one reason he had been neglected was that he wrote like no one else: a pioneer of unconventional poetry in the language. Maybe it is for poetry that he is a subject of contempt. If he hadn’t become famous, his coolness would’ve been lost in history. Like Michael Madhusudan, Rabindranath, and Nazrul, he too had his own brand of uniqueness. Their views on life, religion and belief, even their subject matter and literary style, were all unique to them. These four chief-priests of Bengali poetry had all arrived through unconventional means. They were anti-establishment, and, in that sense, rebellious and against the coteries.

However, the damage to Jibanananda had already occurred. There have been stories of how he was so embarrassed of confrontation that he would take a longer path just to avoid people he knew. He would go sit on the lone chair in the house, violating etiquette. It was said that he’d stay up all night to hear the sound of dew. These select eccentricities may have been true, but can we believe that Eliot’s devotees and Tagore-worshippers always spoke the utmost truth? Moreover, when many of his contemporaries were taking up posts as diplomats, Jibanananda had remained only a poet. Miroslav Holub was an immunologist, Neruda an ambassador, and Niccanor Parra a physicist. While it is hard to believe that Jibanananda was forced to withdraw from everything he attempted, this is something we must accept. Lavanya Das, his wife, had opposed this image of passivity: “When I hear these things, it surprises me, for I don’t recognize this as him. I’m unaware of an inert Jibanananda that I’m told about,” she said.

All of Jibanananda Das’s diverse and huge literature hasn’t reached us yet. The information we do have, thanks to the tireless work of literary researchers and critics, such as Abdul Mannan Syed, tells us that Jibanananda had a deeper sense of emotional pull than most of his contemporaries. Yet the poet’s image is disappointing and calls for a deliberation. One did not see Christ himself offer the other cheek when he was slapped on one in the film, The Last Temptation of Christ. Such was his personal investment in rebellion that he couldn’t side-step any pardon. His crucifixion was sedition.

Jibanananda Das had lived during a time of great upheaval in the Indian subcontinent. Two World Wars were fought during this time. A Marxist, socialist state was established in Russia, bringing widespread change in the political landscape of the globe. Groundbreaking scientific innovation lay the foundations of a new dawn. Moreover, there were the eventful days of the independence movement, especially the nationalist and internationalist movements that took place in the early half of the twentieth century.

The rise of Fascism in Europe and the Bolsheviks in Russia, the revolutions in China and the expansionist policies of imperial Japan—one could find nationalist thought gaining momentum in every part of the world, from Latin America to Africa. One could argue that this nationalist zeal arose in part from the internationalism beginning to be felt around the world at that time. In the midst of a time like this, perhaps it’s understandable that the most masterful poet in the Indian subcontinent could be forgotten. Why else would we call him a poet of Beautiful Bengal? Was the poet himself satisfied with this image created of him? If this was the case, why didn’t his manuscript of Beautiful Bengal see the light of day during his time. Though written in the forties, it came out in the sixties, three years after his death in 1954.

Analysis of Jibanananda Das is often hindered by asking whether he should be labelled the poet of solitude or the poet of Beautiful Bengal. What had Jibanananda Das done that we had to dig out his works even fifty years after his death. He had, really, tried to take us through the complexities of man and matter, of mortality and immortality, of the pain of eternal relationships, of how we may not be masters of our own minds and thoughts. He had helped us negotiate the web of language that riddled our minds. Even now there are many we aren’t acquainted with. The poet had questioned whether there was any difference between the prey and the predator. He had said: “How far are they from Vaikuntha and hell? The mouse goes laughing with a bolt, the cat gobbles it up in revolt.”

Perhaps we should take a moment to clarify our stance regarding Jibanananda Das’s nationalism and internationalism. It’s a discussion made from an international perspective and language. Political fame here has always been irrelevant for the poet. Though nationalism has a political and geographic component, in the context of poetry internationalism is geared towards universalism. Nepal Chandra Majumder had written two volumes of works on Rabindranath’s nationalism and internationalism. Of course, with Tagore, internationalism did come to mean something in the political sense. Rabindranath thought of the world political order at length, inaugurating an internationalism in the intellectual sphere. He had praised and condemned the political systems of both Europe and Asia throughout. We have learned about those experiences during his travels to America and China.

Jibanananda, however, had probably never been out of the Indian subcontinent. Still, he was a wanderer his entire life — a sailor and horseman. Seeing him in this context could’ve given some respite to his image. The Indian lands had always lacked two of these components of war: horses and a navy. This has been a significant reason for the inferior army of Bengal. The land had always been ruled by the lord of the horses and the seas. But as a fugitive in riverine Barisal, Jibanananda Das yearned for the horse and the sea. Wanderlust and hunting are principle themes in his works, where the pervasive desire to travel was universalized. Such desires often remain latent in one’s life, expressed only occasionally. However, Jibanananda Das was able to materialize this sensibility. In his writings, we see horses of various shades, white and grey, roaming the vast wilderness of antiquity.

The poet discovers what’s in the human heart — capturing with words the omnipresent cry of a lover, the mother’s love for her child, and the longing for the body’s immortality. The depth of his art is measured by the intensity of the conflict between style and content. In this regard, there isn’t much difference between poets of today and those of five thousand years ago. Even the Greek Poet Homer can be compared with the Bengali poet Muhammad Sagir. Priam’s wailing at his son Hector’s death in the Iliad is not any different from Yakub’s cries at losing his son in Yusof-Julekha. Priam had begged for the return of his son’s body. Yakub had professed of converting to any religion that would bring a dead son back. It is often said that great men think alike; perhaps, that also is the case for great poets, whose ideologies undoubtedly arrive from their nation and contemporaries. This is the reason why the poet Sagir had brought the Israelite Yakub to the Indian plains in his works, and made Julekha and idol-worshipper.

In this sense, Jibanananda Das is fully nationalist and internationalist in sensibility and expression. One or two examples can be provided here to drive the point home. The poet thought about death and universalism, but his mode of expression was dependent on the nation. In the words of Tagore, though he did force language a bit too much into his works, yet even then this rendered his works too difficult for appraisal in any other tongue. Because what he said were merely words in the end. It could not reach the deeper crevices of the reader’s mind. The words could not travel on their own. They arrived with the help of Bengal’s rivers and vast plains, on the back of the horses, in the stars studied by astrologers and on tram lines. In this sense, he may have been a bit too nationalistic. Even more so than his contemporary Jasimuddin, famously known as a pastoral poet. Jasimuddin was adept at using all manner of tricks to mold the language. But Jibanananda’s works, sometimes fast-paced, sometimes lethargic, were immersed in the nature of Bengal.

He talked about the milestones he’d accomplished with the publication of The Grey Manuscript:

Had I never taken the farmer’s plow in my hand,

Never drew water from a bucket?

The times I went to the fields with a sickle,

The river docks to fish

I had turned

The moss of the pond; the sweat clinging to my back

Its smell envelops

Other than his Fallen Feathers phase, Jibanananda Das was never vocal about the underlying issues of the time. Still, the misdeeds of the then-colonial rule, the prejudice of the Bengal of the past, the call for the triumphs of the soldiers of freedom are ever present in his poems. He had written about Mahatma Gandhi, Chittaranjan Das, and had dedicated his books to political leaders such as Humayun Kabir. Stalin, Nehru, Freud and Marx, among others, had found their way into his poetry. His nationalist credentials become obvious with his tributes to the heroes of liberation, famine, and communal riots. Jibanananda Das’s poetry wanders the edges of the world while we come to terms with the complexities that the poet had wrought inside our hearts.

The following is an example of the poet’s nationalist and internationalist geo-political thinking:

This city could be of any nation, of any identity

Today the human race is at the pinnacle of decay

In the noise of endless traffic, factories, trucks and cranes

What the heart had lost it calls

Mechanically from the beyond

“Are you Greece, Poland, Czech, Parish, Munich

Tokyo, Rome, New York, Kremlin, Atlantic,

London, China, Delhi, Egypt, Karachi, Palestine?

One death, One role, one law.”

The machine says. The captain speaks up:

“All the land must be built anew

In the history I have made,

The limits of the new time – it’s all my doing.

I preserve their touch, present them their rights

I am the union of all our people – blood, yellow, blue

Green, white, obscene.

The Laws must be revoked with black

Chase them away with grey bricks

The crowd of my followers are a bar of darkness

What, then, is the light of the insular family

Jibanananda Das explored a world exhausted after waging two world wars. He had lived not just a poet’s life, but also gave an answer to how man could survive amidst dictatorial machines on a horrific, futile planet: “Knowing of the smokeless joy in our bones/ we float away in the muddy waters of time.” The degraded man of the contemporary world also come up in his poetry: “The leper laps up water off the Hydrant/Or it could be that the Hydrant had got stuck.”

Such discussions do not carry much importance for a poet of Jibanananda Das’s caliber. Yet it is undeniable that the reader loves the harmony his words carry and how they signify the relations of their own lives. Jibanananda Das did not keep himself far from the national and international politics that poets of his era busied themselves in, especially Rabindranath and Nazrul. Even Madhusudan, the pioneer of modernity in Bengali poetry, had his Meghnath Bod Kavya reflect the times he lived in.

A number of poets had established themselves in the world market of Europe and the Americas around his time: T.S. Eliot, W.B. Yeats, John Crowe Ransom, Hart Crane, Ogden Nash, W.H. Auden, Stephen Spender, Dylan Thomas, Robert Lowell, Walker Gibson, Nicolas Guillen, Pablo Armando Fernandez, César Vallejo, and Carlos Oquendo de Amat. One could find the influence of Eliot on Jibanananda Das. He was a decade older than Das, but was also able to leave his mark on English poetry at the time. Rabindranath had translated a few of Eliot’s works. A lapsed catholic, he had the attention of atheists as well as vaishanavas.

Our understanding of world poetry has principally been through translation. Poetry from languages other than English was only known about through the limited understanding of English. One can say that in translation poetry is diminished, since the translator has to relinquish the elegance and prosody of the original. Yet it is also true that since antiquity most of the great literature has reached us through this transcreation. The poet’s own language not only pulls the reader toward him but also creates barriers. A poet’s style is often able to influence the reader of his own language, whereas in the case of poets in foreign tongue we rely on the material itself to enjoy the work. The Mahabharata and many other epics had reached us through translation. Even T.S. Eliot’s allusions, his code switching and mixing do nothing for Bengali reader as long as we are not acquainted with their meanings. Eliot is separated from readers due to the diglossia apparent in the language. Therefore, translation is quite necessary if the literature is to leave a mark.

But who must take responsibility for translating the language of a subjugated people? Rabindranath had translated The Gitanjali himself, when wanting to have his English acquaintances read his works. It is often said that Yeats had helped him in this regard, polishing the poet’s English, but that is a complete lie. There is no reason to undermine Rabindranath’s grasp of the English language. It should have been more proper for Yeats to translate Tagore’s works. However, being a speaker of the Master’s tongue prevented him from doing this. Moreover, though he was three decades younger than Tagore, he had his own works translated by Tagore.

If the light of translation had fallen on Jibanananda Das, his worth would have been priceless to the international community. Perhaps this could have helped his financial difficulties as well. Jibanananda, too, considered his poetic life to be part of society at large. He had said, “The poet must have faith in talent, for one day the world would require his work to help sow the heart in the fields of immortality.” But how will this union take place? Was there any way other than through translation? The pleasures we find in reading Eliot come from our discoveries of what his words mean. Does Jibanananda’s work reveal itself to us in the same way?

I began this essay by talking about Jibanananda writing in English. It has been more than sixty years since his death. English still dominates as an international language. The poet had once said in a discussion on the future of Bengali language and literature that “English was going away. Hindi is becoming a state language. Compared to English, Hindi is weak, made for poor literature.” He had always considered Bengali to be stronger in this regard. But since English is considered the language of knowledge and science, it would obviously remain in its privileged position. Still in his essay, “English in Education and Literature,” he said, “Most educated people in this country have little taste or understanding of English literature. They don’t have the power to talk of these things genuinely. It is the same in the case of Bengali literature. The Bengalis should strive better to know Bengali literature more so than English literature.”

None of Jibanananda’s nationalism and internationalism has gone beyond the scope of logic. In an essay, “Logic, Inquiry and the Bengali,” he stated, “America, Britain, Soviet Russia — today all the countries in the world are nationalistic.” Yet he also thought that it wasn’t possible for a country to achieve its maximum development solely through nationalistic pursuits. “It’s impossible to change a particular nation’s idea and way of working,” he had said, “without changing what’s in its heart.”

Return to Journal

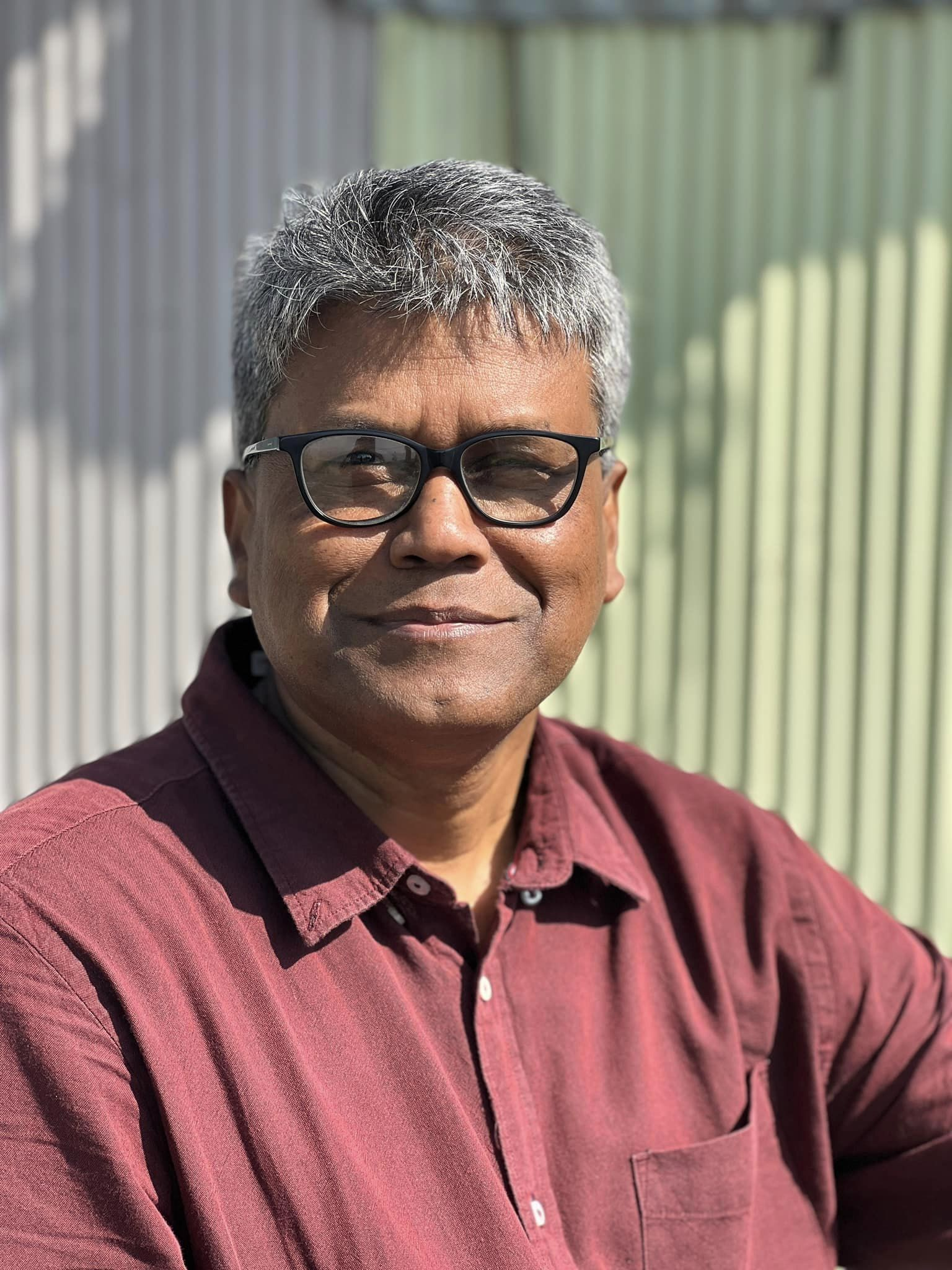

Mozid Mahmud is a poet, novelist, and essayist based in Bangladesh. Some of his notable works include In Praise of Muhfuza (1989), Nazrul – Spokesman of the Third World (1996), and Rabindranath’s Travelogues (2010). Mahmud was awarded the Rabindra-Nazrul Literary Prize and the country’s National Press Club Award, among others.

WordCity Literary Journal is provided free to readers from all around the world, and there is no cost to writers submitting their work. Substantial time and expertise goes into each issue, and if you would like to contribute to those efforts, and the costs associated with maintaining this site, we thank you for your support.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly