Maybe Yes, Maybe No

Chapter 1

I’m sitting in one of my favourite places, our balcony overlooking Mud Lake. Afternoon rays warm my skin. A green smell wafts up from the trees that stretch as high as my floor. Birds I don’t recognize sing nearby. For once, the loud voices in the apartments around me have fallen silent. And then, music sounds from the heat vent just inside the door. Heavy metal. Like the vent. But it’s muted, as though someone’s speakers aren’t working. I’ve been hearing sounds like this for three, maybe four, months. My head nods, and my feet tap to the beat. Someone in one of the apartments must have a high-end system. Probably stolen.

I grab an apple and a granola bar from the kitchen. Taking a bite of apple, I stuff the bar into my hoodie pocket and head for Britannia Beach. It’s a great place to swim, except that, every year, idiots get caught in the current and swept downstream. I’ve seen the Zodiacs go out looking for them—and come back with lumpy body bags.

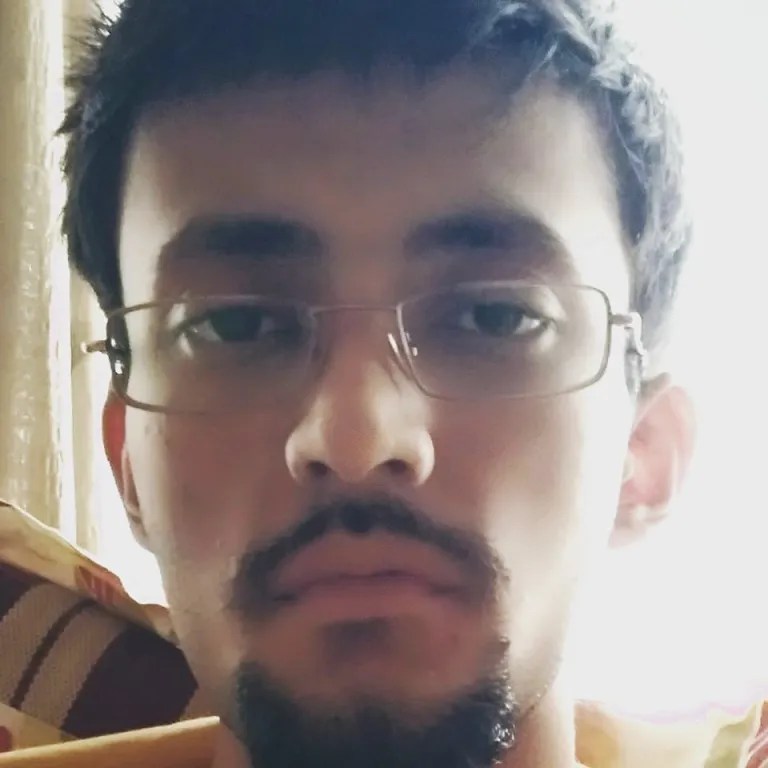

Sticking to the bike path, I walk as far as the picnic shelter. Khalid’s already there, left leg forward as he does some post-run stretches. His dark hair shields his face with its shaped eyebrows, smoky eyes, and purple-tinged lips. Khalid and I have been best buds for as long as I can remember. I used to worry that our friendship would get all mixed up with the boy/girl thing, but I don’t anymore. Two years ago, when we were fifteen, Khalid told me a secret I’m not allowed to tell anyone else—until he’s ready.

Hey, I made a promise, and I’ve kept it.

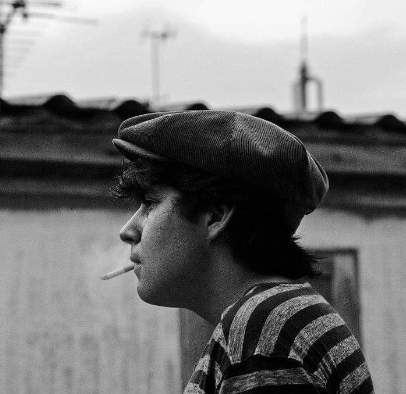

Khalid finishes his stretches, and we head toward the pier. Today, Khalid jitters like he wants to talk. I don’t ask what about because I need a smoke. Hands trembling, I search through my pockets. Only lint because I promised Mom I’d quit when she insisted smoking would make me more likely to get type 2 diabetes like her. Also, she claimed that watching me savour a cigarette made it harder for her not to reach for one.

So, I stopped. At least around Mom.

I don’t smoke cigs anymore. But I mooch them, mainly from Neil, who hangs out on the street and in the woods around Mud Lake.

“Come on.” I grab Khalid’s hand and drag him onto the Mud Lake trail. A bunch of little kids block the path, all with their hands over their heads. They stand straight and still, holding out black sunflower seeds on flat hands.

A chickadee flits to one girl and pecks a seed from her outstretched palm. I grab my cell to try for a pic. Just when I’m focused, a kid’s hand blocks my shot. Damn. But shit, they’re just kids.

Khalid and I wait for them to run out of seeds before squeezing by, careful not to step off the path into poison ivy. The stuff doesn’t stop Mud Lake from attracting loads of visitors. Most go to see the birds. Occasionally, an otter—okay, that’s not a bird—sneaks in from the river for easy-to-catch fish. That’s when the shore sprouts with lenses as long as my arm.

I lead the way to the spot by the lookout where Neil and his dog, Sweetie Pie, are building a teepee. When I was little, I used to sit in shelters like that and pretend I lived in the bush. No traffic. No drunks screaming. No drug dealers in the halls.

A thin haze rises from Neil’s partially built structure. Sweetie Pie, ears pricked, rests in the coils of the dragon tattoo on Neil’s left arm. She’s a black and tan dog small enough to fit between his elbow and wrist. I say she’s a snug-a-muff—large enough to snuggle and small enough to keep Neil’s hands warm during the winter.

Today, Neil peers out at Khalid and me, a cigarette hanging from his lips. Neil’s tall, dark, and a regular at Fries ‘R Us, where I work.

“How ya doing?” He offers me a smoke.

I grab it, my hands trembling. It’s been too long. Neil stands, lights mine from his, and offers Khalid one. He refuses, which is no surprise. Khalid’s working toward a marathon.

Sweetie Pie, plumed tail wagging, comes to say hello. “How’s my sweetheart?” I ask as I scratch the kinky hair on her ears. She sticks out her pink tongue and gives a toothy grin.

Neil grabs her rainbow collar when a Wood Duck lands on a tree nearby. It’s a male with loads of bright colours: green, white, black, blue, red, beige, orange. The shades shimmer like they’re alive.

I take a relaxing puff. Hold it in and count to ten. But the duck’s colours still flicker like a television screen gone bad. Nothing new. I’ve seen weird things like this for several months.

“Nice colours on that duck,” I say.

“I’d love an outfit like that,” Khalid offers.

“All shimmery like that?” I ask.

“That would be even better.”

Sometimes, Khalid combines shades I’d never think to use together. And they look great. He has a knack for that. Style.

Neil shrugs. “The colours just look ordinary to me.”

He must notice different things than I do, like when Mom got sick and went into a coma. I knew something was up when she drank glass after glass of water. Then her breath started to smell sweet and fruity, kinda like nail polish remover.

I made myself talk to Mom about it one evening while we watched TV, ate Oreo cookies, and guzzled Wild Cherry Pepsi. Mom said she felt weird. When she got up to pee, I heard a crash in the bathroom. She was flat on the floor, gasping like a fish out of water. I called 9-1-1. Fast. They took her to the Ottawa Civic Hospital. That’s when we learned she had diabetes. Remembering the whole thing makes my heart pound.

“Relax,” I tell myself and take another puff. I feel calmer until I glance at my watch. Four-thirty. I need to scram if I’m going to make my five o’clock shift at Fries ‘R Us.

Chapter 2

I’m panting as I reach Regina Towers, the fancy name for the run-down government housing where cockroaches, bedbugs, and I live. As usual, the elevator’s not working. Damn. Taking three steps at a time, I race up four floors and run inside. Now, the vent is silent. Who knows why?

Shrugging, I throw on a leaf-green, short-sleeved cotton shirt over my black pants. Then, I roll my apron and hat into a ball and stuff them into my backpack. I bag my smoky clothes and toss them under the sofa. Finally, I tear open the granola bar I’ve kept in my hoodie. As I munch, I check the kitchen cupboards to see if anything else interesting has appeared.

Nope.

A roach sits beside Mom’s test strips for blood sugar. I smash it with my fist and flush the corpse down the toilet—to make sure it’s dead. The bugs have been so common during the last two years that they no longer gross me out.

I grab my Foundations 11 text so I can do my homework during break and run downstairs. An Ottawa Transpo bus idles just outside the door. I could save time by taking it. But Fries ‘R Us is only four stops away. Better to run, even if it’s all uphill, and keep that cash for my photography course at Algonquin College.

Before stepping behind the Fries ‘R Us counter, I don the full-length brown apron with a giant potato at the bottom and Fries ‘R Us in gold stretched across the chest. Now, I resemble a giant spud. Embarrassing, but not as bad as the leaf-green cap with its brown visor and Fries ‘R Us in gold on the front and back. I hate that people see me wearing this stuff. But the pay’s good. And the owner, Ramsee El-Dib, is easy to get along with.

“We need you on cash. STAT,” she says. As usual, her flamingo-coloured hair is trying to escape from her cap. “Take over from Mercier.” Ramsee’s silver tongue stud peaks out when she speaks.

“Got it.” I dump my purse in lock-up before moving to the centre cash register.

Mercier grins when I arrive. “Thanks.”

I shift from foot to foot as she signs off the register so I can take control. Since it’s the beginning of the dinner rush, people have already lined up. Two of them jiggle impatiently. I step up to the counter and fake a smile for the first customer. “Welcome to Fries ‘R Us. May I take your order?”

I can hardly hear the woman. It’s like we have a poor connection.

“Could you say that again, please?” I strain to make out her words and repeat them as I key in the order. Once she swipes her card, I grab the receipt, pack the grub, and hand it across. “Thank you for coming to Fries ‘R Us.”

The next hour goes by in a flurry of greetings, burgers, fries, and drinks. Fries are our specialty—everything from home-cut ones with malt vinegar and salt to poutine with Montreal smoked meat and perogies plus cheese curds and gravy. We also have a list of spiced fry flavours: chilli or cumin fries, fries with mayo, and even some with basil, cilantro, parsley, oregano, and garlic powder. I prefer fries with aioli—that’s garlic and oil, the way my New Zealand cousin eats them.

I’m really into the swing when Neil’s voice sounds from the register on my left. “What do you mean I can’t have bacon ‘n eggs on fries? I’ve had them here lots of times.”

My stomach sinks, and I look across. Sure enough, he’s even got Sweetie Pie curled in the curve of his arm. Won’t Ramsee love that!

Jazz, the cashier, stands square as if that might make his 5’ 4″ frame look taller and heavier than it is. “I’m sorry, sir,” he says. “We stopped serving our breakfast menu at 11:00 a.m. Would you like some poutine? That has cheese curds on it.”

“No!” Neil’s voice starts low but rises in volume. “I want two servings of bacon ‘n eggs on fries, with the eggs sunny side up, so the yolks run over the fries. Put the bacon on top. Mm. Parfait.” Hands trembling slightly, he places his thumb and forefinger together and kisses the air.

Ramsee steps up beside Jazz, her lips so tight you can’t see her tongue piercing. “I’m sorry, sir,” she says. “We put away the breakfast ingredients mid-morning and don’t start serving breakfast again until five a.m. We could make you some poutine with double cheese if you like.” She glares at Sweetie Pie, who smiles back. “We allow only service dogs in this food establishment.”

Expecting an explosion, I turn away. I don’t want Neil to see me or be hit by his shrapnel.

Neil blasts out our opening greeting. “Welcome to Fries ‘R Us.”

Uh, oh. There he goes.

“But don’t expect to get what you want. I want to enjoy EGGS with my EMOTIONAL SUPPORT DOG.”

The customer in front of me snorts with laughter.

Ramsee’s cheeks turn as pink as her hair. “If you order, I could serve you outside,” she says. “Would you like to try fries with mayo and spicy peanut sauce? Mayonnaise has eggs in it. And I’m experimenting with that combination, so it’s free. Taste it and let me know what you think.”

Neil’s face screws up. “Peanuts? Are you trying to poison me? You shouldn’t be called Fries ‘R Us. You’re Spies ‘R Us and trying to kill me. I want bacon, eggs, and fries.”

Ramsee comes out from behind the counter.

I hold my breath, worried about what Neil might do.

“I’m sorry, sir,” she says. “You don’t want cheese with fries, so I was trying to offer a protein you like. I had no idea that you were allergic to peanuts.” She points across the road, her smile brave. “There’s a grocery store over there. They have a deli section, so might be able to help you. But I don’t think they’ll allow your pup without a Service Dog vest.”

Neil’s lips tighten. When Sweetie Pie reaches up and licks them, Neil blows her off. He looks my way as he turns to go.

Uh oh.

“Brandi!”

I hide my face in the chilli and cumin fries I’m preparing.

Neil steps toward me. “They’re trying to kill me. But I can trust you. Please make me some bacon ‘n eggs on fries.”

My face heats up. “I’m sorry, sir. I’m not the cook.”

Sweetie Pie yips. Neil puts a hand over her nose and then gives me the finger. “It’s a conspiracy, and you’re in on it. See what happens the next time you ask for a cigarette.” Neil flings himself toward the door, muttering about spies searching his apartment.

His hand slams against the exit door’s glass panel, leaving a long crack. Then, he flips another bird while Sweetie Pie nuzzles at his neck and face, trying to calm him. I could use a dog like that right now. Breathing deeply, I focus on not strangling my used-to-be smoking buddy. My voice trembles as I greet the next person in line. “Welcome to Fries ‘R Us. How may I help you?”

Chapter 3

After Neil went ballistic, the place was so busy that I missed my break, which means I didn’t do my math homework. Friday, I endure back-to-back classes until noon—no time to figure out how to do my algebra assignment. I can do it—but need time. Lucky math’s the first period after lunch. In the caf, I munch on tasteless fries while struggling with the formulas. Why isn’t my brain working today?

But hey, I have the evening off, and Mom promised to pick up dinner from Shawarma Garlic and Onion. Yum. Maybe she’ll forget about her diabetes and add baklava to the order. Maybe I’ll guilt-trip her into letting me have all of it. Double yum.

Friday means lots of food, and I haven’t run into Khalid all day, so I text him.

< Join us for dinner? 6? >

< Sure. Got something special to show you. >

< What? >

< You’ll see. There in 5. >

No one locks the main lobby entry in Regina Towers, so anyone can come up the stairs and into our unit. Still, I’m shocked when a stranger opens our door and poses against the frame, brown hand on one hip. “So, what do you think?”

“Who are—” I move to push her out. Wait. On her hand, green, indigo, and violet wink from a Pride insignia.

My jaw drops. “Khalid?”

Well, not Khalid. This person wears a fitted red dress that moulds to his—I mean her—or is it their—body? I like the Mandarin collar. And, wow, the painted pink cheeks and puckered red lips are amazing, as is the fine, straight hair that cascades down her back. I wish my hair would grow like that instead of in its kinky brown mass.

Khalid’s dress ends at mid-thigh, showing off a terrific pair of legs. Guess that’s from the running she does most nights.

Khalid grins. “Meet Dawn,” she says.

“Where’d you get that dress?”

“Online.” She—definitely she—pirouettes around the room, arms out. “What do you think?”

“Amazing. I would never have dreamed—”

Dawn grins again. “Like I’ve been born in the wrong body and finally emerged?”

She’s right about that.

Dawn’s never had much facial hair. Today, there’s no sign of any. She’s arched and thinned her eyebrows. Her red lips pout like some movie diva’s. Charcoal liner circles her shining eyes.

Mom doesn’t bat an eye when she comes in with her arms full of bags. “Khalid,” she says with a big smile. “Or have you changed your name, too?” Mom’s a stylist at a place the clients call Queerios, so she’s into this.

“Dawn.”

“That’s beautiful. And your pronouns?”

Why didn’t I think to ask? My cheeks get hot.

“They. Them.”

When Mom unpacks dinner, the pungent aroma of cumin in the chicken and beef shawarma rises from the bag. Drooling, I grab plates and cutlery, set the table, and point at the wraps full of roasted meat and other goodies.

“Help yourself, Kha-Dawn.”

“Do they all have the same toppings?” they ask.

I nod with my mouth full.

“Tomatoes, red onions, pickles, pickled turnips, parsley,” Mom says. “With tahini sauce. Hope you’re not allergic.” She takes a huge bite.

“I’m not.” My eyes water from so many onions. When I swallow, my stomach sends happy vibrations.

“Me neither.” Dawn takes dainty bites, so different from Khalid’s chomps. “Thank you, Mrs. Herbert.”

Pounding vent music starts up during dinner. “That music’s way too loud,” I complain. “It gives me a headache.”

Dawn peers around the room. “What music?”

My head bumps up and down to the catchy rhythm. “Can’t you hear the thump?”

Mom shakes her head. Dawn pulls out her smartphone. “Here’s my kind of vibe.” Strains of Pink Suits, their favourite group, drown out the beat from the vent.

“Right.” My fingers go numb when I lift a beef and garlic wrap to my mouth. The food tumbles down the front of my sleeveless crop top, into my lap, and onto the floor. Damn. When I bend over to retrieve it, I lose my balance and fall over. Double damn.

Mom’s green eyes pop out from her pale face. “Brandi, are you alright?”

I push to my feet. “I think so.”

My head goes in circles, and I stumble when I try to pick up the mess. Dawn grabs one of my arms, and Mom takes the other. Together, they guide me to the sofa.

Although I try to stop, I can’t help shaking. What an idiot I am. I’ve turned into a baby who can’t eat properly.

“Why don’t you lie down?” Mom cleans up my food while Dawn clears the table, and I watch from the sofa. A breeze blows across my arm, making the hairs stand at attention. It’s so cold.

Dawn slinks across and sinks beside me. “I’m sorry. I have to go.” They peer at me with a worried expression. “I need to change back before Dad comes home.” They take my hand and squeeze it. “But I don’t want to leave you.”

“It’s okay. I’m alright.” I grip their warm hand with my cold one. “See you soon.”

Dawn drapes my favourite sunflower quilt around my shoulders. “Tomorrow. For sure.” They whisper something to Mom on the way out.

Frigid air trickles down my neck like a cold shower. I use the flowered throw to try to block it. Beyond the balcony door, people wander along the street wearing shorts and T-shirts—or short dresses like Dawn’s. How come I’m so cold?

“Mom, can you get me another blanket?” I ask.

Mom pulls up the woollen cover I leave at the foot of my sofa bed and tucks it around my torso. “Is this enough, honey?”

I huddle under it and the sunflower quilt. Better, but not enough against the polar storm that blasts me, even with the balcony door shut. It feels like the air conditioner’s on. When I check, it isn’t. I press against the back of the sofa and try to block the draft coming from who-knows-where.

“I’m freezing,” I whimper.

Mom grabs another blanket. “I’ll be right back,” she says, heading for the door.

“Don’t leave me,” I whine.

Droplets of perspiration drip from Mom’s chin. “Back in two shakes,” she says.

I pull the two covers tighter—and continue to tremble. When Mom finally returns, she adds a duvet warm from the dryer to everything already on top of me. “How’s that?”

The heat soaks into my body. “Better.”

But only for a few minutes. Even though layers of cozy blankets wrap around me, I can’t get warm.

Mom brings more cosy throws fresh from the dryer. After the third delivery, her voice breaks when she asks, “Better?”

Not really. Frigid air continues to rob my heat and energy. If I could block it— A box might do it, one that covers my entire upper body. Except that the ones in recycling would likely have roaches or bedbugs. So, I continue to huddle on the sofa until—

I don’t know how to explain what happens next.

Somewhere inside my head, a door shuts, and everything goes blank.

Chapter 4

HELP! I can’t see.

But I can feel. I’m tucked into a cylinder and can’t move. HELP! My heart pounds double time.

A hum approaches. It gets louder and stops right beside me. Is it after me? I hold my breath, expecting I’m-not-sure-what. The noise moves away, and I try to calm my breathing. In. Out.

Nearby, a machine goes whish, whish, and then clicks. Something—or someone wheezes. I can breathe. I’m alive. Warm. Sweating. And terrified.

Something snakes from my elbow to the back of my hand. Nearby, papers rustle. That mechanical breathing continues. And a loud whoosh.

My hands tremble, and my breathing stops. Did I take off in a spaceship?

I can’t feel any movement, but you don’t in a plane either. Maybe we’ll land on an exciting planet. Or revolve around the Earth doing who-knows-what. I have no idea because I’m unable to see. The portholes must be dark. But there’s sound. And feeling. And fear.

My heart thumps. How long will it take to get where we’re going? And what will happen once we do?

My breath sucks in and hisses out; my skin creeps with goosebumps. My eyes continue to see nothing.

And then I go out again.

Voices wake me. I’m lying on my back, with pillows holding me in place. Somewhere behind me, a machine continues to gasp and pound. Soft-soled shoes hurry past, followed by more swishing. The squeak of rubber wheels stops beside me and then continues to who-knows-where.

“This one came in on Friday night,” someone says.

“Catatonic. On CO,” says the other.

Cata what? And who’s the CO?

I open my eyes and look around. I’m lying on a stretcher with my head raised on one—no two—pillows. I’m in a hallway. My bed’s at a T-intersection where three halls meet. To my left is a nursing station where someone in blue-flowered scrubs taps on an out-of-sight keyboard.

A woman in charcoal scrubs stands beside me. She reaches up towards a bag hanging on a post almost out of sight and adjusts something on the tube that goes down into my arm. “So, you’ve come back to us.” Her blue eyes are thoughtful.

I shift my head, mouth quirked. “Where was I?”

She doesn’t answer.

Pale light shines through the long, narrow window beside the nursing station. It must be morning. I struggle to get up. “I have a shift this afternoon.”

The woman stops me. “Easy.” She studies my face. “What day do you think this is?” Her words have a lilt, like maybe she learned English in another country.

“Saturday, of course.”

Her forehead wrinkles. “Today is Monday.”

My mouth drops open. “It can’t be.”

“You’ve been catatonic.” Maybe she thinks her smile is soothing.

“Cat-a what?”

“Catatonic. Semi-conscious.”

So, the door closing has a name. Have I been here in the hospital all along? And lost—I count on my fingers—three days?

A meal cart nudges the woman’s back end. “Is she ready for breakfast?”

The woman in charcoal steps away. “Why not ask her yourself?”

A redhead with a tiny body, like a jockey, picks up a tray and steps forward. She coos like I’m some exhibit in a trans-planetary zoo, “Well, are we all ready for our breakfast?”

Before I can answer, the head of my bed rises, a table slides across my lap, and a tray lands on top. I’m starved but can’t face the glop in the bowl in front of me. I drink the little plastic jug of urine-coloured juice and start to force down the cold, dry toast. Better than nothing.

I’m five bites into the toast when Mom rushes around the corner carrying a Tim Hortons cup—likely a double-double. Her shoulder-length mushroom-brown hair looks like she swept it with a broom. Her eyes are puffy. “I’ve been so worried.” After placing her cup beside my breakfast, she latches onto my hand, the one with the needle. “Are you okay?”

“Sure, I’m fine.” What else can I say?

Mom slides a chair toward my bed and continues to clutch my hand. She sips coffee, and I munch toast until the nurse with blue-flowered scrubs comes around the end of her counter. “Welcome back,” she says. “It’s so good to meet you.”

Yeah, right. I smile like I’m thrilled to be stuck in a hospital bed.

“We’ve had you near the nursing station because you needed to be on CO,” the nurse says.

“CO? Like in carbon monoxide from car exhaust?”

Mom pats my hand. Her skin is grey, like she hasn’t slept for three nights. She knuckles both eyes and says, “Constant observation. They didn’t know what was going on with you, so they wanted you close—in case.”

In case what?

The nurse doesn’t give me time to ask. She smiles encouragingly. “Once you’ve finished breakfast, we can take you to your room.” Her perky voice sounds like a cheerleader’s. “And once that’s done,” she continues, patting Mom’s shoulder, “why don’t you go home for a rest?”

Mom rears back. “Not until we see Dr. Lee again.”

Again? “Who’s Dr. Lee?”

It’s like neither Mom nor the nurse hear me as they roll me down to a single room and tuck me into a bed too far from the window to look out. Mom shoves a bag of clothes into the bedside table and puts a toothbrush, hairbrush, and deodorant in the drawer.

“I’m not staying,” I say when a man with a Dr. Lee nametag enters. “I feel FINE. So, my brain needed a rest. It’s okay now. I have to work my shifts if I’m going to college.”

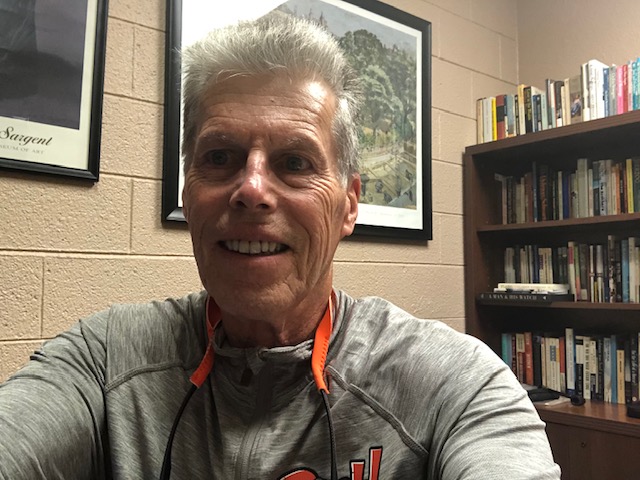

Dr. Lee is even taller than Neil, who tops six feet. But Neil is always clean-shaven, while Dr. Lee could use a razor, even mid-morning. “We can’t make you stay,” he says, “because you don’t seem to be a danger to yourself or anyone else.”

Yay! I get a choice.

“But we don’t know what made you go catatonic.” He clears his throat. “It might suggest a mood disorder.”

“Mood disorder?” I yell, my eyes brimming with tears. “Like a mental illness? I pass out, and now I’m in cuckoo land?” It wasn’t me who slammed out of Fries ‘R Us. It was Neil. I just—quietly—went out. I take a deep breath to calm myself.

Mom swallows and glares at Dr. Lee. “When we talked before, you asked if Brandi was on drugs. Now you’re saying she has a mental health problem. Are you sure it’s that?” Her voice shakes. “And not a diabetic coma?”

Dr. Lee fingers the stethoscope hanging over his bright white lab coat. “ER did blood tests when she arrived, Mrs. Herbert. Her blood sugar levels were fine.”

I’m not sure whether to be relieved or annoyed. Diabetes is a pain. Just ask Mom. But mental illness? Am I going to think I’m God and everyone should follow me? Or that the police are after me? Or fear I’ll drown if I have a bath or that people will poison me if I eat their food?

Although my hands shake, I force myself to speak calmly. “I feel fine now. Except for an empty stomach.”

Dr. Lee wrinkles his nose. “Didn’t they give you breakfast?”

I offer him my leftover toast. “How many meals have you eaten here?”

He grins. “Enough to know they’re not gourmet.” He looks at Mom and then at me. “Look, I know it’s a shock to hear you might have a psychiatric disorder.” Tell me about it. “We’d like to keep you for a few days. Long enough for us to figure out what caused your catatonia and how to prevent it from recurring.”

Tears stream down Mom’s face. “You didn’t say this might happen again. Oh my God, I can’t handle that.”

“It won’t.” I throw back the covers, swing my legs over the side of the bed, and stand. “I’m fine now. And going home.”

Dr. Lee sighs. “I can’t force you to stay.”

I clap my hands together. “Which I’m not.”

I raise my hands, palms up. “Please, Mom,” I plead. “There’s nothing wrong with me. Tell him how I keep up on schoolwork and also work part-time.”

Both Mom’s body and voice shake. “Dr. Lee, you said Brandi might have a mood disorder. Like what?”

Dr. Lee pulls at the sleeve of his white coat. “About one-third of the people who get catatonia like this also have bipolar disorder.”

Mom moans. “Like Kanye West?” She gulps. “He’s made such a spectacle of himself.” There’s a brief pause. “How long does it take to test for bipolar disorder?”

Dr. Lee fingers his stethoscope. “That’s the problem. There is no test. We can rule out physical conditions but can’t diagnose whether or not someone has bipolar disorder.”

I reach for the clothes Mom put in the bedside table. “I’m out of here.”

Chapter 5

“Wait.” Dr. Lee moves his tall bulk between the bedside table and me. “If you could just stay long enough for us to observe you. And listen to what you say about how you feel and what you do. That will help us make a diagnosis.”

I roll my eyes. “I feel fine now. Can’t you treat me as an outpatient?”

I turn to Mom, my eyes imploring. “They treated your diabetes outside the hospital, didn’t they? All those online courses that taught you how to eat right.” I wrinkle my nose at Dr. Lee. “You should have seen the meals she learned to serve. How many ways can you eat avocado?”

Mom blushes. Dr. Lee chuckles.

Ignoring a little vent music, I repeat, “I’m fine.”

Mom doesn’t argue, so I know I’m getting to her.

I stretch to my full five six. “Mom, Dr. Lee says that tests can’t diagnose bipolar disorder. And they’ve already checked my blood to rule out other stuff. I don’t want to miss work. Or school.”

Two good hits.

“And I promise to cooperate with any treatment.” Which is better than she did at first. One morning, she cooked gigantic pancakes she smothered with butter and fake maple syrup—guaranteed sugar high. I won’t do that.

Mom caves. “I’d like you to work with Brandi as an outpatient,” she tells Dr. Lee.

He tucks his stethoscope firmly into his pocket. “I can’t force her to stay. I’ll arrange an appointment at the Pinecrest-Queensway Community Health Centre.” He speeds away.

I wrap my arms around Mom. “Thank you.”

I change into the clothes Mom brought. As we pass the nurse’s desk on our way out, an attendant gives Mom a prescription for me. “This should handle things until we get a complete analysis,” she says.

We pick up some blue and white capsules on the way home. I take one before bed.

The following morning, the sofa prickles like I’m lying on thistles. I huddle under the covers, listening to Mom make breakfast. “Why don’t you just rest for the day?” she suggests before heading to Queerios to style the hair of a client she missed while I was in hospital.

I stare out the balcony door, my energy level at zero. My bladder forces me to get up. I have a pee and dig around the kitchen for that paper the pharmacist told me to read. “May cause fatigue,” jumps off the page. So, it’s the pill. Taking one blue and white pill has zapped my energy. I collapse back onto my sofa bed.

At some point, I push myself to my feet and drag my body to the kitchen again. Balanced on a cheap folding chair, I stare at the cracked bowl of cereal Mom left for me. Resting my chin on my fist, I count the spidery cracks. One. Two. Three. My head drops onto the table as I try to gather enough energy to pour milk into the bowl. Even though the jug rests beside my hand, I can’t tip it.

I sit and stare at nothing.

When the afternoon sun moves around to the balcony door, I haul myself up and prepare to go out. I sleep in a sweatshirt and joggers, so just need to pull on socks and running shoes. The leaf-strewn trails around Mud Lake are almost deserted. I drag myself as far as Neil’s pine shelter. Sure enough, he’s there, his face as clean-shaven as ever.

“Hey.” He offers me a cigarette, his hand shaking. Vibrant blues flow around Neil’s close-cropped hair—the colours pulse as though alive. “Where’ve you been?” he asks.

I shake my head, and his aura disappears. “In hospital. They gave me some pills.”

“You too?” He pulls out a red and white vial that reads Tylenol Extra Strength. “Like these?” He opens the container and pours different-coloured pills into his hand: red, white, blue and white, yellow and green, pink.

“Those don’t look like Tylenol.”

He shrugs. “It’s just the container. The doctor gave me all of these. He said they’d keep me sane.”

“Do they?”

He slides his quivering fingers along Sweetie Pie’s silky ears. “They make me stupid, so I stopped taking them.” He forms his hand into a funnel and returns the pills to the vial.

Maybe I’m right about those blue and white things. “I think mine make me tired.”

“Some do that if you take them,” Neil says.

I didn’t. “The pharmacist said it’s important to follow the directions on the vial,” I say.

Neil continues to pet Sweetie Pie. “All part of the Big Pharma conspiracy. You don’t take pills; they don’t make money. You always do what you’re told?”

“Well, no. But—”

Neil yells, “But nothing.” Sweetie Pie gives a slight hum and nuzzles his neck. “You don’t have to take those pills.”

If bipolar disorder is like diabetes, I could get into trouble without medication. Mom takes insulin and watches her blood sugar levels. If she’s not careful, she could go into a coma. But I could take a chance and dump these pills. What harm would it do? Without them, I’d have more energy—enough to go to school and work.

Work! I haven’t called Ramsee. Will she believe me when I explain? I pull out my cell and dial. “Hi. Ramsee? It’s Brandi.” I hold my breath. Beside me, Sweetie Pie licks Neil’s chin.

“Brandi. I’ve been worried. What’s up?”

How does she sound? Angry? Uncertain? I take a big breath. “I’ve been in hospital since Friday.”

“That’s terrible. Are you okay now?”

Does she want the truth? I doubt it.

“Sure. I’m fine,” I say. “Look, I’m sorry about not calling, but I was completely out of it.” Talk about an understatement. “I’m back now. What’s my schedule?”

Ramsee clears her throat. “Jazz has a family emergency. So, we could use someone starting at five.”

“Meaning me?”

“If you can.”

“I’ll be there.”

I push to my feet and steady myself with a palm against Neil’s favourite pine. “See ya later. I gotta get to work.”

Chapter 6

I stumble home, where I change into my wrinkled uniform that reeks of chip grease. Too tired to run—or walk—I take the bus up the hill to Fries ‘R Us. Ramsee meets me at the door. “Glad you got here so soon.” She removes her Fries ‘R Us cap and scrambles her pink hair. “We’ve got an early rush. Think you can handle it?”

I look at the long lines at each register and force a smile. “I’ll do my best.”

The shift moves as slowly as math class. My sluggish fingers type in the orders, accept the payment, and fill the bags. I deliver them with a languid thank you.

Some customers have blue auras like Neil’s. Others have red, orange, and yellow ones, like my uniform. How many people can see stuff like that?

When my break finally arrives, I dawdle into the kitchen. “Make me a large fry,” I ask Greta, the cook. “Puhlease.”

She drops a handful of fresh-cut potatoes into the basket and lowers it into the fryer. Almost three minutes later, she pulls them out, releasing that wonderful aroma that makes me drool.

“Now, can you put them on a sesame bun with a scoop of ice cream?”

When Greta laughs, her lined face sprouts furrows that go down her neck. But I’m more interested in the gigantic bun she loads with large fries before adding a scoop of Death by Chocolate ice cream. “How’s this?” she asks, handing it to me.

“One hundred percent.” Clutching it to my chest, I thread my way through the customers to the door. Outside, I lean against the warm brick of the Thrift Store beside Fries ‘R Us and start to eat. Someone cheers nearby. “One. Two. Three. Four. Who are we for? French fries. French fries. Rah. Rah. Rah.” It sounds so much like one of the school’s cheerleaders that my eyes search for blue and gold pleated skirts.

Not here. Weird.

I close my eyes and snooze in the warm sun until a honking car on the road nearby jerks me awake. The last of my ice cream has melted onto the pavement. I wipe it up and head inside, where I toss my soiled napkins into the garbage behind the counter.

By the end of my shift, I’m wiped. I take the bus home, where Mom reminds me about my night pill. My hand shakes as I drop the blue and white capsule into my palm, swallow it, and then wash it down with water. What will it do this time? Make me tired? Or stupid, like Neil said?

I lie on my sofa bed, waiting for one of the reactions to kick in. Instead, my nerves jangle like I’ve drunk too much soda, and I can’t get to sleep. I roll around my sofa bed, cuddle in my blankets, throw them off, and then wrap them around me again. Finally, I get up and sit on the balcony, watching people drive in and out of the Regina Towers parking lot. Someone above me screams swear words at every vehicle. I feel like doing that, too—just for the fun of it, but don’t want to wake Mom.

After who-knows-how-long, I go back inside and root around for a book. Mom’s left one on the toilet tank: Everybody Poops 410 Pounds a Year. Potty humour. Great. I perch on the toilet, turn a page, and learn that a flush can send poop particles two metres into the air. Gross. I move my toothbrush inside the medicine cabinet before reading further. John Harington invented the toilet back in the time of Queen Elizabeth I. That’s why we call it a John. And Thomas Crapper, a plumber, popularized toilets during the late 1800s. American soldiers during World War I saw T. Crapper on the toilets and started calling them crappers. So that’s why we crap. Imagine.

I read forever, but still can’t sleep. Can one blue and white capsule do this? Should I wake Mom to tell her?

At some point, I put away Everybody Poops 410 Pounds a Year and make my way back to my sofa bed. I lie there staring at the ceiling. The streetlight in the parking lot throws finger shadows across the pockmarked paint. I eyeball them until the morning sun filters through the sheers.

Despite the lack of sleep, I’m full of energy. I bop around the kitchen, making blueberry pancakes. I eat a stack with butter and real maple syrup before leaving the rest for Mom, who’s on the afternoon shift. Then, I dance down the hall to the bathroom holding my towel and undies. I stand under the shower until the skin on my fingers wrinkles. Instead of going to school, I wander down to Mud Lake.

Dawn’s lounging near the entrance. Today, they wear a mini denim skirt so short it’s like a pair of short shorts. A gray T-shirt with a scoop neck and three-quarter sleeves hugs their top. They rush across and wrap me in a tight hug. “Your Mom said you were okay, but I’ve been so worried.”

“Don’t worry about me.” I give them a big squeeze. “What about you? Why aren’t you at school?”

They shrug. “I wanted to try out this outfit. But not at school.” They pose against a tree. “How does it look?”

“Super.”

Dawn bites their lip. “I wish Dad thought so.”

“Maybe he’ll get used to it.”

“Maybe.” They don’t sound convinced.

We walk as far as the bridge, where a great blue heron stands on long, spindly legs, its yellow eyes focused on the water. One second, it’s frozen. The next, it strikes. When the bird slowly straightens its long neck, a black catfish disappears down its gullet. One humongous swallow and the heron freezes again, watching for a second course.

I grab my cell phone and catch a repeat.

“What’s up?” Neil slouches against the rail at the other end of the walkway.

I motion him away. “Shh, I’m trying to get a shot of this heron fishing. Don’t scare it.” I hold my phone at arm’s length. “Look how clear the bird is. You can see every feather.”

Without looking at my picture, Neil scratches Sweetie Pie’s ears. “No big deal,” he says. “It’s here every day. You can get it tomorrow if you miss it today.”

The heron stands almost up to his belly in water. His reflection stares back at him like a frozen twin. My cell captures him that way. After showing the photo to Dawn and Neil, I aim my cell again.

A squirrel runs across the bridge railing and churrs at Sweetie Pie, who starts to bark. The heron raises his head. As he dips his neck, his wings go up. By the second downbeat, only the tips of his long toes trail across the water. I yell at Neil to shut his dog the fuck up as I take several quick shots. I look at the new pics and can’t believe I caught the movement.

I show them to Dawn. “I was trying for some award-winning photographs. What do you think?”

“You got ’em.” Dawn grabs my hand. “Dad’s at work. Let’s photoshop them on his home computer.”

I can almost taste the headline: Celebrity Photographer Brandi Herbert Gets Start at Mud Lake.

Chapter 7

Dawn leads the way back to their condo, their rear sashaying from side to side in their tight mini. The lobby is bright and clean. When Dawn calls an elevator, one quickly arrives. They play with their necklace as we ascend to the fifteenth floor. Their view, which is mainly over the residential streets leading to a nearby mall, isn’t as good as mine. But Dawn’s dad has a spare office in an alcove off their living room. My nerves quiver as we download my photos onto his computer and start to play. These are going to be so good.

I crop my fave so the great blue heron takes up the entire screen. Then, I experiment with filters. One brings out its blue tones and turns the water into a liquid mirror. Every feather comes into sharp focus when I play with the clarity setting.

I show the result to Dawn. “This one’s pretty good.”

“That’s an understatement,” they say, waving toward the monitor. “Let’s see the rest.”

Within an hour, I have five fantastic shots.

I google ‘where to sell nature photos’ and run my finger down the top fifteen. “Wow!” I squeal. “If I market these shots right, I can make enough to buy a two-bedroom apartment. And we can move in together.” My words tumble over themselves.

Dawn chews on their beads. “Or maybe quit your job?”

Work!

I check the time. Twenty minutes until my shift starts. I can’t be late.

I save my photoshopped great blue heron pics in the cloud and hug Dawn. “Gotta go.”

A key clicks in the front door lock.

Dawn runs for their bedroom. “Dad’s early. I need to transform. Fast. See you later.”

On the way out, I say hello to Mr. Habib, who’s coming in. “Why aren’t you in school?” he demands, his dark eyes glaring.

I lie, hoping he doesn’t check. “Professional Development Day. Dawn and I were hanging out.”

“You mean Khalid,” he grinds out.

Without answering, I squeeze by Mr. Habib, run down the hall, and take the steps because they’re faster than any elevator.

Lucky I’m wired because the elevator in my building next door is still out. I sprint up the four flights of stairs, throw on my work clothes, and jog up the hill to Fries ‘R Us. It’s incredible how good I feel as I hurry inside. Who’d know I haven’t slept in 30 hours?

Ramsee greets me at the front door when I arrive, panting. “Right on time,” she says. Her dark eyebrows wing across her face, making her pink hair appear even pinker.

I rush by her to put my things away. Moving like a high-speed robot, I serve one customer after another, chat brightly, and hardly listen to their responses. I don’t remember ever feeling so good. Ecstasy—and I don’t mean the drug—stays with me through the entire dinner rush.

When Ramsee asks me to clean the lobby, I quickly sweep the floor with its crumpled napkins, bent straws, and even a condom still in its wrapper. Using a pair of gloves, I pick it up, hold it at arm’s length, and drop it into the garbage bin.

A little girl with the family by the gas fireplace throws herself on the floor. Her spilled juice drips from the table onto her seat and, from there, onto her denim top. The father tries to wipe the liquid off her blouse but only smears the mess further. “Don’t worry.” He tries to soothe her. “We’ll get you another one.”

At high speed, I swab the table and the place she was sitting before grabbing a pail and bucket to mop the floor. She watches from her father’s lap as I work, her big eyes round in her brown face. I wink at her. Quick like a bunny, I haul the used trays to the back, clean the rest of the tables, and sponge the floor. I’m revving high. If those blue and white capsules can do this, I’ll take them forever.

Ramsee gives me a thumbs up when I return the pail and mop. “You’re really on tonight.”

“Sure am.” I skip to the register, where a customer asks for fries without salt. I notify Greta, who deep-fries a fresh batch. But when I hand across his order, the customer asks for several salt packets. Another of those idiots who wants his fries extra fresh. What else does he think he’ll get here?

Outside, the sun starts to sink. Good. My shift’s almost over. I count most of my bills and paperclip them together. That’ll make it easier to do my tally later. The drive-through’s so busy that Ramsee asks the other cashier to help there, leaving me to serve the walk-ins.

Two teens leave, and a man bustles in. He carries a camera with a lens about as long as my leg. Wow.

“That’s some camera,” I say instead of my usual spiel. “Were you at Mud Lake?”

He grins and turns the camera body to display its LCD screen. “Yep. Mud Lake’s about the best place in Ottawa to see birds.” He shows me a blue-green bird with piercing eyes and a pointy beak.

“Wow.” I look up at the man’s wispy gray hair and smile-creased face. “What is that?”

“A green heron.”

From the name, it must be some cousin of my great blue. It doesn’t look it, though. Still, I smile. “I’m a photographer too. Well, I take photographs.” Fantastic ones.

Ramsee rushes through from the kitchen then, so I switch to being a Fries ‘R Us server.

“Welcome to Fries ‘R Us. May I take your order?” I ask.

“Sure. Large fries, double salt, and a large French Vanilla cap to go. Now, what were you saying about photography?”

Ramsee’s back in the kitchen. I babble as I check the order, key it in, take his money, and pack his food. “I live almost beside Mud Lake and go there regularly. Got a terrific shot of a great blue heron this week. Hope to sell it.”

The man gives me a business card when I pass across his order. “I teach photography at Algonquin College. Why don’t you send me a copy of your photo? Maybe I’ll have some suggestions for you.”

Algonquin College? Where I plan to go? I grab the card and read it—Rick Nakamura, Professor. “Sure thing. I’ll send some right after work.” I give a fist pump and slip the card into my pocket. With his help, my photo will go viral. It might even sell to a photo agency that ends up hiring me. Yes!

Chapter 8

Bright daylight nudges me awake the following morning. I get up, pee, yawn, and then huddle beneath the covers. The next thing I know, Mom’s calling.

“Come on, Brandi. Up and at ’em. You have an appointment with Dr. Kitsch this morning.”

I squeeze my eyes closed and moan, “I’m too tired to see a psychiatrist. Phone and tell her I’m fine.”

No way will Mom do that. She hustles me out of bed and into the shower. “I’ll get your breakfast.”

A soft-boiled egg with a bright yellow yolk that oozes across buttered brown toast waits on a chipped plate on the kitchen table. Beside it sits a plastic bowl of blueberries. Okay, I can stomach those.

After breakfast, Mom and I walk to the Pinecrest-Queensway Community Health Centre, with me lagging.

“Come on,” Mom says, dragging at my arm. But my feet refuse to hurry.

A receptionist sends Mom and me upstairs to Dr. Kitsch’s office. I’m so tired my legs almost give out halfway.

Dr. Kitsch is tiny, has wiry hair cut close to her round head, and wears a blue jacket over a black pullover. The outfit seems overkill until I feel cold air blast from the heater. In October? I shiver in my sleeveless tee and light cotton leggings.

“The heat pump’s not working properly,” Dr. Kitsch explains. “Let me get you a sweater.” She scurries out and returns with a zipped gray hoodie that sports a rainbow across the front. “How’s this?”

I pull it on with relief. “Good.”

“So, you must be Brandi Herbert?”

“Yes.” I can’t see Dr. Kitsch’s eyes through her tinted lenses.

“And this is your mother? Mrs. Herbert?”

Mom plays with something in her pocket. “Thank you for seeing us. We’ve been anxious to talk to you.”

Not me. I want Dr. Kitsch to say I’m fine and let me go. I dig my nails into my palms to stay awake.

Dr. Kitsch’s glance moves from my borrowed hoodie to the black scrubs Mom wears for her hair stylist job. “This must be a difficult time for both of you.”

“It is.” Mom’s voice hits high soprano.

“Do you mind answering some questions?” the doctor asks me.

Since I don’t have much choice, I shrug a sullen yes.

Dr. Kitsch looks at me and poses a pencil over the clipboard in her hand. “I’d like to understand how you’ve been the last two or three months. For each of the following questions, can you tell me whether you never do it or do it either sometimes or often?”

That sounds easy. I shrug again. “I guess.”

“How often do you complain of aches or pains?” She looks across at me.

That’s an easy one. Not often. Except for that stomach ache last week. “Sometimes.”

“How often do you tire easily?”

I frown. “With a part-time job on top of school? Come on. Sometimes.”

“How often do you fidget or have problems sitting still?”

One of my feet has been jerking since I sat down. “When did you last have to sit through a boring class?” I ask, thinking of Mr. Yauk, who can make the most exciting novel put you to sleep. “Sometimes.”

The questions continue. “How often do you daydream too much?”

What’s too much? Does it include imagining how soon I can refuse to stick around for useless questions like this? “Never.”

“How often do you feel hopeless?”

Only when I’m stuck in a room like this. “Sometimes.”

“How often do you have trouble sleeping?”

Wasn’t I just deep under for three days? “Never.”

“How often do you want to be with a parent more often than before?”

At 17? Come on. I enjoy Mom in small doses. And Dad? Well, I never knew him. “Never.”

The questions go on and on. Nothing about hearing vent music. Nothing about seeing colours glow. I relax because I’m acing this test. They have only one thing on me—that cata-thing. And maybe it was a fluke.

The overhead lights glint off of Dr. Kitsch’s gold earrings. “How has your energy been?”

“Well, I manage to go to school, work part-time, and take pictures at Mud Lake.” Clearly, nothing’s wrong.

Mom interrupts. “Sometimes I think she does too much.”

Shut up, Mom.

Dr. Kitsch’s painted-on eyebrows arch. “How do you mean?”

What’s she thinking beneath those tinted lenses?

“Sometimes Brandi’s full of energy.” Mom eyes me. “At other times, she crashes. Like this morning. I had a hard time getting her up.”

Dr. Kitsch wrinkles her nose. “Teens do need eight to ten hours of sleep every day.”

Way to go, Doc. “I did a long shift yesterday,” I say. “I’m working at Fries ‘R Us to earn my college tuition.”

Dr. Kitsch beams. “You sound like a daughter to be proud of.”

Mom picks at her cuticles. “I am proud of Brandi,” she says without looking up.

There’s a small mole on the end of Dr. Kitsch’s chin. “Are there times when you’re revved? Like you’re on an upper?” she asks me.

I shake my head. “Nope.” Except for yesterday when I sped around Fries ‘R Us wiping tables, sweeping and mopping floors, and taking trays to the kitchen. It was like I’d drunk too much Red Bull. “Well, maybe once or twice.”

“I’ll bet that felt good,” she says.

It did.

She looks directly at me. “Energy like that might suggest hypomania. Usually, we can handle something like that outside the hospital.”

Like I said to Dr. Lee.

“But if it continues—” Dr. Kitsch gives me a mini-lecture. “Certain lifestyle choices can help you keep your life balanced.” She rambles on about the importance of regular healthy meals, a good night’s sleep, and planned exercise. Yada yada. It’s almost like she’s been listening to Mom’s lectures on diabetes care. What would the doctor think of my fry and ice cream sandwiches, something Ramsee should add to her menu?

Dr. Kitsch finishes her lecture and hands across two prescriptions. Like a short quiz and mini lecture would help her figure out what I need.

“I think these will help prevent a recurrence of the ups and downs you’ve been having,” she says. “Take one of each before bed each night.”

Mom drops the prescription at the drugstore on the way home and pays to fill it so I can pick it up during my work break.

Chapter 9

That evening, Dawn jogs into Fries’ R Us at the end of the dinner rush. They wear ripped denim capris with a scooped-neck tee. A metal male/female symbol hangs around their neck. In case Ramsee’s listening, I give them a thumbs up and swing into my spiel.

“Welcome to Fries’ R Us. May I take your order?”

“I’d like something filling,” Dawn says. “What would you suggest?” Without taking a breath, they continue. “How did things go with your psychiatrist?”

I shrug. “She doesn’t think I need to be in hospital.”

Dawn grins. “Right on.”

“But she prescribed two more medications.” Ramsee and her pink hair are coming through the kitchen door, so I add. “Our all-time best-seller is our fries with cumin.”

“Give me a large, please.”

I key that in as Dawn asks. “And did you send what’s-his-name the great blue heron pics?”

I huff on my fingernails and polish them on the Fries’ R Us logo on my brown apron. “The three best. He wants to meet with me.”

Dawn squeals and then covers their mouth. “Put double salt on those fries, please. What else is popular?” They turn serious. “Have you agreed?”

“Our second most popular item is our double hamburger with bacon, lettuce, and tomato.” Like they don’t already know. “I want to meet him, but is it safe? He says he’s a teacher. What if he’s not?”

“Thank you. I’ll have a double hamburger—loaded except for pickles.” Dawn continues in the same tone as if they were ordering. “You could link up at my place. Or what about here? When you’re slow.” She fake-studies the menu board. “And I’d like something sweet. What do you recommend?”

It’s weird having a dual conversation like this. “Greta makes the best double chocolate brownies each morning. Hard to beat them.” I add, “Things slow down between three and four. We could do it then when I’m off.”

“Great. I’ll take one double chocolate brownie and a small root beer. Do you want me at a nearby table when the prof comes?”

Ramsee hurries out of the kitchen on one of her regular checks. “You’re Khalid, aren’t you?” She raises her hand with her middle fingers folded, but her forefinger and little finger straight up and her thumb out.

Dawn gives her the same LGBTQIA+ sign. “My name is Dawn.”

Ramsee half-smiles and turns to me. “You’re spending a lot of time with Dawn here, which is no problem if people aren’t waiting. But don’t push it. Okay?”

“We won’t.” Dawn turns back to me. “Do you have my order?”

“Yep.” I finish keying it in, accept the payment, and start packing the food.

When they pick up the bag, Dawn whispers, “Text me when you’ve arranged a time.”

“Gotya.”

With Ramsee watching, I clean the counter around my cash before going onto the floor, where I wipe the tables. Next, I swab the tiles by the bathrooms, order kiosks, and fireplace. When it gets busy again, Ramsee signals me back to the cash.

During my break, I text Mr. Nakamura. He gets right back. < See ya at 10 Sat am. >

Then I go to pick up my prescriptions, two new meds. That night, I take one of the blue and white capsules Dr. Lee prescribed and one of the small pink pills from Dr. Kitsch. They go down easy with a glass of water. The other new pill is a fat, oval tablet that’s too big and hard to swallow. I roll it in toilet paper and tuck it into my pocket. Who says I need it anyway?

Chapter 10

Friday night, I get the best sleep I’ve had in weeks. I wake up after dawn and lie on my sofa bed, thinking about the day ahead. I’m seeing Mr. Nakamura today. What should I wear? I try on and reject a dozen outfits before deciding on a thigh-length white cotton dress with blue trim around the hem and V-neck. I add gladiator sandals laced up my calf. That feels good— until I look in the mirror, where I see a teen with blue eyes and kinky brown hair wearing a dress that maybe belongs on the beach. I tear it off and change into a cotton blouse with three-quarter sleeves. Black pants are safe. I put on an ankle-length pair.

In the kitchen, I say good morning to Mom and pour cereal. When I try to swallow the first mouthful, my stomach heaves. Mom suggests a piece of dry toast, but my gut’s too nervous for that, too. I gulp some juice and brush my teeth. At least my breath will smell sweet. I put on a gold chain with an emergency whistle at the last minute. Okay, maybe that’s overdoing it. But how do I know how safe I’ll be?

My nerves buzz as I hurry up the Poulin Avenue hill, the whistle banging against my chest.

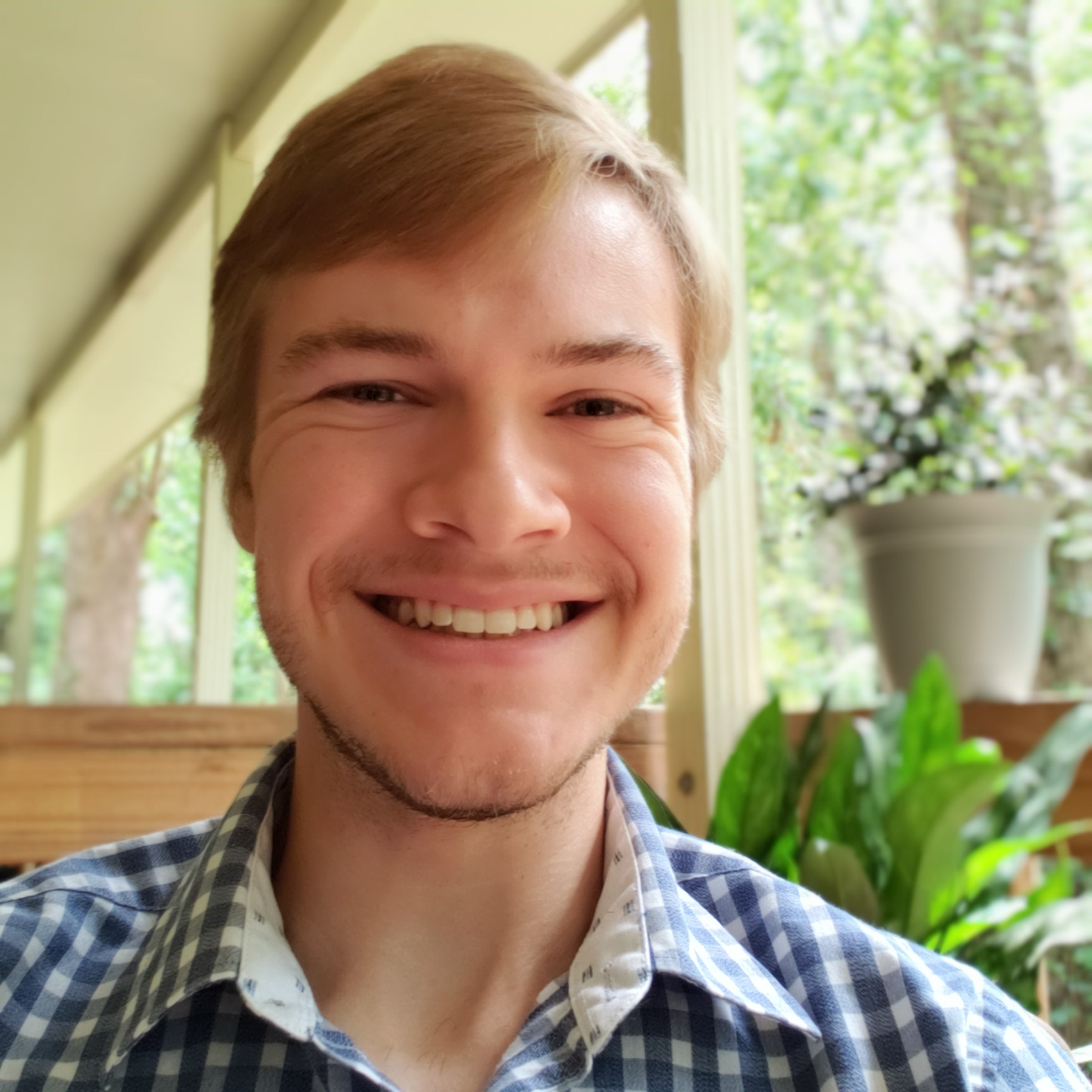

Mr. Nakamura sits in front of the cold gas fireplace, a black camera bag with a Canon logo beside him. He stands up and offers his hand. “Brandi. Thanks for coming.” His steel gray hair is parted in the centre. His bushy eyebrows are the same colour. His handshake is firm.

After checking for Dawn, who’s eating at the table behind Mr. Nakamura, I slide onto the chair across from him. There are large fries, double salt, and a large French Vanilla cap in front of him—same as last time. A large fry with mayo and curry and a large milkshake container sit by me. Even though the fries are close to my fave, I can’t stomach food right now. But the milkshake. At his nod, I take a sip. Death by Chocolate Triple Thick. How did he know?

When Mr. Nakamura smiles, his gums pull back from his yellow teeth. “I told the cashier who I was meeting and asked what you liked best.”

Mercier’s at the counter, watching with her usual grin. “Sorry, we’re out of aioli.”

I give her a thumbs-up for the milkshake.

“So, what do you think of my pics?” I ask Mr. Nakamura.

He beams. “They’re good.”

My mood soars.

“For cell phone shots,” he adds.

That’s a downer.

He pushes the black bag across to me. “You have a good eye, which is why I contacted you. If you could take pictures like that with a cell phone, imagine what you could do with the proper equipment.”

I sigh. “If I could afford it. But I can’t. Not with college tuition coming up.”

He looks me straight in the face. “There are scholarship programs.”

“Not for me. My marks aren’t high enough.”

“I can help with the equipment.” Mr. Nakamura pulls stuff from his camera bag, and my jaw drops. The camera looks new. The lens is as long as my forearm. Wow.

“These have been sitting in my closet for months,” Mr. Nakamura says.

What a waste. I have to stop my hand from grabbing the stuff. “So, why’d you bring them?” My eyebrows rise like my voice.

He smiles. “For you. On loan. For as long as you need them.”

“For me? There must be a catch.” There’s always a catch.

He leans against his chair back and gives me a sideways grin. Light from outside reflects off his glasses. “Someone helped me when I was starting. I’m passing on the favour.”

I pick up the camera before Mr. Nakamura changes his mind. I aim at Mercier by the counter and fumble to focus. Everything’s blurred.

“You’re too close,” he says. “This is a long-distance lens. Meant especially for wildlife.”

I aim at a pickup across the parking lot, which is about the distance that the great blue heron was. Something sits on the vehicle’s hood. I focus on that. A ram’s head comes into view so clear it feels like I could touch it. My hands shake with excitement. Imagine bringing a bird this close. My shots would be so good I’d win competitions. Maybe make enough to pay all my tuition. Yes!

Across the table, Mr. Nakamura pulls an Instruction Manual, an extra battery, a charger, and even a card reader out of his magic bag. “I think you’ll need these, too,” he says, showing me how to use them.

Is he Santa Claus or what? “Why me?” I ask.

He shrugs. “You have talent.”

Behind him, Dawn gives multiple thumbs-ups.

I tremble as I pack everything back into the bag. “I don’t know what to say.”

“How about thank you?”

“How can I thank you?”

“By using them. Show me what you can do.”

I wonder if this might be a hallucination and wait for everything to disappear.

But it doesn’t.

Chapter 11

I gulp one blue and white capsule and a tiny pink pill before bed on Saturday night. They go down easy. I stuff the fat oval tablet into my pants pocket. That night, I sleep but wake up exhausted like something’s siphoning my energy. Except that Google says teens need ten hours of sleep, and I’ve had only seven and a half. ‘Course, I’m tired. So, I bury myself in the warm cave under the covers. I huddle there until it’s time to drag myself up the Poulin Avenue hill to Fries ‘R Us for the evening shift. But I’m not much good that night, and Ramsee finally sends me packing. She won’t fire me. She’s already so short-staffed she needs me.

At home, Mom’s watching TV in her bedroom and doesn’t notice anything wrong. Good. I take two of my three meds, drag myself to bed, and sleep in my uniform, which reeks of sweat and fry oil. At eight Monday morning, Mom comes into the living room in her pyjamas. “Rise and shine, Brandi. You don’t want to be late for school.” Her bright voice grates against my ears.

I’ve been in bed for over ten hours, can’t remember how much I slept, and want to stay here forever.

Mom rips off my blanket. “Come on.” Her voice is insistent.

Although wiped, I push myself off the sofa and stagger down the hall to the bathroom. After a long pee, I peel off my uniform and stumble into the shower. Cold water still leaves me draggy, so I switch to warm and let it run over my head, face, and back before shampooing my kinky brown hair. I reach for the crème rinse, but the bottle’s empty. Damn. I burst into tears. “Mom, we’re out of rinse,” I wail. When I stamp my foot, the bathtub rumbles. “Why don’t I just go back to bed?”

Mom’s at the door. “Calm down, honey. I’ll make something up.”

I drip while kitchen cupboard doors bang. A tap turns on and off. A couple of minutes later, Mom hands me a measuring cup that smells like something I’d put over one of Ramsee’s specials. Yuck. It’s either that or snarled knots, so I pour the stuff over my head, wait a few minutes, rinse, and then fish for a towel. Of course, it’s not on the rack. Damn! Can’t Mom do anything right? I grope my way over the bathtub rim, fumble under the sink, and grab a fresh one.

Mom’s at the bathroom door again, this time with my clothes. “Come on, dear. You’re going to be late.”

Will you give me a break?

When she shakes out my slacks, several flat white tablets as large as footballs tumble across the floor. Mom picks them up and stares.

Uh oh.

“BRANDI!” Her voice goes up three octaves. “Have you taken any of the pills Dr. Lee and Dr. Kitsch prescribed?”

“Yes.” My voice quivers.

“What are these then?”

I whisper. “The ones I didn’t take.”

Her voice gets louder. “What?”

I shriek, “I can’t swallow them.” My spittle lands on Mom’s arm. Okay, I didn’t mean to do that. “I don’t need them anyway.”

Mom collapses against the vanity. “You sleep in your clothes, smell like a deep fryer, and have a fit when we run out of hair rinse. You call that fine?” Her eyes dagger into me. “When did you stop taking these?”

My hands shake as much as my voice. “I never did. I don’t need them. Mom, can’t you see that I’m fine? I haven’t missed a day of school yet.”

Mom shakes her head. “Yeah, sure.” She waits for me to dress, follows me to the kitchen, and hands me one of the footballs. “Down the hatch.”

“It’s too big. It’ll make me puke,” I say.

She places the thing on a cutting board and cuts it in half with a serrated knife.

“Still too big,” I whimper.

Mom cuts it in half again and watches me scarf the four pieces down with water, her green eyes wide with anger. “I’m going to watch you swallow your pills every morning and every night.”

“But I feel good without them all. Never better,” I say. Sure, I’m tired. Google says that’s normal for teens.

Mom bites her lip. “There’s something wrong, Brandi. You know what the doctors said.”

Shut up. Shut up. Shut up. “I feel fine. Except tired.”

At school, I hunch over my desk, hardly hearing what the teachers say. Why do I need math if I’m going to be a photographer?

After school, the camera demands a trip to Mud Lake. But the strap digs into my neck, and I can’t see straight. Why bother, anyway? I’ll never take a prize-winning photo, even with Mr. Nakamura’s fancy stuff.

That night, Mom’s out, and I’m so tired I forget to take any pills. They’re making me crazy anyway. And tired. It’s all the fault of Dr. Lee and Dr. Kitsch. They must have something against me.

After school, I drag my way up the Poulin Avenue hill to work. Neil sits in the sun outside the drugstore beside Fries ‘R Us. Sweetie’s curled up beside where his cell phone is plugged into an outside socket.

“Hey, how ya doin’?” He offers me a smoke.

I light and inhale. “Thanks,” I say on the exhale. “Things are kinda crazy. Mom found out I haven’t been taking all my meds.”

Neil shrugs. “Good on you.”

Another puff. “Mom doesn’t think so.”

Neil peers at me. His eyes are wider today and almost black. “Maybe it’s not your mom.”

I can’t help shivering. “Of course, it’s Mom.”

Neil shakes his head. “Could be her doppelganger.”

“Doppel-what?”

“Doppelganger. A double. They’re all over.” He glances toward the street and shivers. “They send out doppelgangers to control us. Your medication probably has trackers to let them know where you are.”

Whoa. “You think Mom has a doppelganger, and I can’t tell?”

Neil reaches down to stroke Sweetie’s ears. “Happens all the time.”

This is getting weird. “Come on. I can recognize my own mother.”

“Not if you were taking their medication.”

My brain is as fuzzy as a television with a poor signal. Could it be the meds? I took two pills the night before last, and Mom forced me to take the third one that morning. But was that really my mother? Neil makes me wonder.

No matter, I gotta go to work. I stub out my cigarette and run toward Fries ‘R Us, where customers line up and give orders. It’s like hearing people talk underwater. Their voices burble, and I have to guess what they mean, often choosing the wrong items.

Ramsee comes across when my lineup stretches almost to the door. “What’s wrong with you?” she asks. Without waiting for an answer, she elbows me aside and takes over my spot.

I lean against the ice cream freezer, the cool steel pressing against my back. That feels good.

Music blares from the Death by Chocolate, my fave flavour. My feet tap to the ice cream’s beat, upping my energy. Good. After a few minutes, I bounce back to the counter.

“I’m okay now,” I tell Ramsee and start to serve.

“Welcome to Fries’ R Us.” My voice is high and cheerful. “May I take your order?”

The customers’ words come in time to the Death by Chocolate’s rhythm. I nod and repeat their requests.

Ramsee watches for several minutes, her brow furrowed, then shrugs and leaves. I greet the next customer. And look up. And up. I’ve never seen anyone so tall. A man with blonde hair to his waist and the thickest false eyelashes. Maybe a trans woman? And then it hits. This is Adrianna Exposée, Ottawa’s première Drag Queen. I’ve seen her online. Whoa, is she something. And even more terrific in person. If only Dawn were here.

“Welcome to Fries’ R Us. May I take your order?”

Adrianna flicks her long blonde hair back over her shoulder. She puckers full lips painted in what Dawn calls rose damask. Adrianna wears an orange sequined dress with a feather boa. Her lids and the area around her eyes are a smoky gray that makes the area pop. No hint of stubble on her carefully highlighted cheeks. And I’ve never seen eyelashes so long and thick—fake, but gorgeous.

I wish I could look like that.

“Nice outfit,” I say.

Adrianna beams, one hand on her waist. “Thank you.” Her voice is a pleasant contralto.

Then, a black wash flows across her colourful outfit, revealing an Ottawa Sens top and matching joggers. I stare and blurt out. “I thought you were a Drag Queen.”

The man’s eyes open in an are-you-crazy expression. “A what?”

Ramsee hurries across and elbows me aside.

“What’s wrong with you today?” she hisses as she takes over.

I open my mouth to answer, but my legs tremble, and I collapse back against the ice cream freezer. Outside, Neil walks across the parking lot. Sweetie isn’t with him. So, is that Neil? Or his doppelganger? How can I tell? Tremors take over my entire body, and I sink to the floor. Maybe Neil’s right. Maybe the pills are making me sick.

Chapter 12

Ramsee tells me to go home and get some sleep. Like I haven’t had enough. But I still feel tired, so I sign out, drag myself down the hill, pull on my “Just nappin'” pyjamas, and fall onto my sofa bed.

When I open my eyes, it’s dark except for the security lights shining on the parking lot. And quiet. No lady on an upstairs balcony is swearing at the cars—because there are no cars. My stomach feels empty, my mouth fuzzy, and I’m tired. Tired. Tired. I pull the covers up and squeeze my eyes shut. My brain tells me to sleep, but my body won’t listen. My hands put on sneakers; my legs take me downstairs. Outside Regina Towers, I follow the street to where another road goes uphill.

I start to climb.

The signs at every intersection jump around in a confusing dance. And then the street starts to slide. Upward. Like an escalator. My head spins. My stomach rumbles. I clap a hand to my mouth and hold my breath until I reach the spot where several streets usually meet. Tonight, they’re changing places. Like the signs. I shiver. This is double weird.

I stand, panting, unsure where to move. Or how. I want to go home but don’t remember the way. I can’t follow the signs because they’re moving all crazy. Huddling against a cement wall, I try to figure out the right direction. Can’t. When I shiver, something hard nudges my hip. My cell. Of course. I grab it and dial 9-1-1.

A female voice asks, “What’s your emergency?”

Should I tell her I’m lost? In my own neighbourhood? I cancel the call and push to my feet, my legs like jelly. My head feels like it might explode. My brain? Gone, I think.

The street beside me moves to the right. My feet hop on and ride to where another road flows down. That’s the way home. I think. On trembling legs, I ride until the avenue suddenly changes direction and moves up. I sway backwards, almost fall, and then race down the up street to a bus shelter. Panting, I grip its smooth glass walls because they’re the only things not moving.

My head spins. My stomach churns. High above me, a full moon shines on the sparkling Ottawa River. The water calls to me. “Come!”

I follow the voice down a shadowed laneway that ends in a stone breakwater where a lifebuoy hangs from a tall post. I step by, pull off my runners, and dig my toes into what I think is soft sand. Sharp pebbles gouge my flesh. Ouch.

Hoping to ease the throbbing, I wade into the chilly water. The current massages my feet and legs. Nice. Lights beckon from across the river. Google says that a colony of greater egrets nest over there. Imagine the pictures I could take. Delighted with the idea, I ignore the cold and surge toward the opposite shore.

A voice nags at my brain. Wait. Wait. You don’t have a camera. Still, I push forward.

The water drags at my legs, almost pulling me down. Raising my arms level with the surface, I lean into the current. It pushes back, trying to topple me. Fear drains the strength from my legs and tries to suffocate me. Still, my body continues to move across the river.

Fingers of frigid water grab my ankles and drag me into a hole. My head goes under. I gulp in water and come up spluttering. Gasping for air, I fight to get back to shore. Although my legs kick and arms flail, the water continues to carry me farther out.

My pyjama pants drag at my legs, pulling me under again. I struggle to kick them away and forget I’m fighting underwater. I take a big breath and come up, spluttering. Beside me, the pyjama bottoms balloon to the surface and float toward the Deschênes Rapids, where an old hydro dam partially blocks the river. Its exposed steel rod could stake me through the heart like a modern vampire.

No!

I open my mouth and shriek, “HELP.” I can barely hear myself over the rushing water.

I scream again, louder, “HELP!”

No response.

“Help. Help. Help.” I focus on screeching and forget to swim. My head sinks under. Gagging, I push to the surface and gasp for breath. The shore’s further away now. I shiver. When I try to kick closer, the current pushes me farther out. Nerves on high alert, I swim with it and yell whenever I get enough air.

No one comes.

My legs and privates are freezing. Again, I shriek for help, the words coming out garbled. Does no one hear?

Wait. I still have my phone. I pull it out. Clutching it like a lifesaver, I turn it on. It’s dead. Shit. Shit. Shit. I drop it into the current.

Will I make tomorrow’s headlines? Teen Dies in River. My heart pounds. My brain screams, “No! Find a way out.”

Like how?

And then, a green glow moves along the bike path that runs by the shore. It’s gotta be some jogger wearing safety gear. Fighting to stay afloat, I use the last of my breath to force out a croaking, “Help.”

The lights turn my way. Hope surges through me, and I rasp another “Help.”

A welcome voice floats across the water, “My gawd, Brandi, is that you?”

Chapter 13

It’s Dawn. Or their doppelganger. Please let Neil be wrong about this.

“Yes, it’s me,” I yell, my voice breaking.

I struggle toward shore. Kick. Stroke. Kick. Stroke. But the more I kick, the farther out the current drags me. How long can I keep this up?

“Hold on,” Dawn calls. “I’ll get a life ring.” The glow from their safety gear speeds in and out near the breakwater. Definitely Dawn.

Hurry. Hurry. Hurry. I struggle to stay above the surface as Dawn returns. Their arm swings. There’s a splash. I stretch for the ring—but it floats downstream out of reach. Hot tears gush from my eyes.

Dawn jerks the ring back to shore. They throw again but don’t reach me, and the current’s tugging me farther out fast. I try to kick, but my legs are numb—like my hands.

Dawn stops under one of the lights edging the beach. I strain to see what they’re holding and miss a stroke. My head goes under. My wet spaghetti arms push for the surface. I swallow a mouthful, and then I’m gasping for breath. Fighting for air, I manage a kick and turn on my back. That’s better, except for my numb legs and arms.

Dawn scrambles over the rocks below the breakwater and follows me as the current carries me farther downstream. “I called 9-1-1,” they shout. “Help is coming.”

I wave to let Dawn know I heard and glug in more water. I try hard to kick and scream, “I need help NOW.” But my numb legs fail me, and I go under again.

I push back to the surface and thrash in the current. Help’s taking too long. I gulp in air for a long scream—and hear sirens. A pickup with flashing lights and a trailer bumping behind speeds along the lighted pathway toward the beach. It brakes in the sand. Dawn jumps up and down on the shore by the lights, pointing at me.

Fluorescent red vests run toward the water.

“HELP!” I wave my arm and go under.

It’s so dark under here. No gleam from either the moon or the lights along the shore. And so cold. It would be easy to stay here. And never come up. Never have to worry about Fries ‘R Us. Or school. Or all those pills.

My foot scrapes the bottom—time to rest.

But my lungs are on fire. I push upwards, searching for the surface—come up gasping.

“Hold on,” calls a female voice. And now the two red vests are in something coming toward me.

Within a few seconds, a paddle reaches for me. “Grab this,” the woman says, “and I’ll pull you in.”

When I stretch for it, the paddle blade becomes two. And when I grab for the top one, my fingers slip through what should be solid wood. I close one eye, tilt my head, and look again. Only one paddle now. I grab the single brown blade. But my useless fingers slide off the wood, and I go under again.

I push myself up and, panting, hook my wrist around the paddle’s edge. My arm slides off.

“I can’t do it,” I sob. My head sinks under as I inhale for another howl. Water fills my mouth, nose, and throat. Choking, I thrash to the surface. A giant donut sails past my shoulder as my eyes come above the water.

A female voice calls, “I’m pulling the ring towards you. Put your arm through the hole.”

When the lifesaving donut nudges my shoulder blade, I struggle to lift a leaden arm but can’t get it high enough. Instead, I hook my elbow through the hole in the middle. That brings my head up and out of the water so I can collapse over the life ring.

The rope attached to the ring vibrates. “I’m going to pull you toward me,” the woman says. “Okay?”

“Ogay.”

Cold water ripples along my lower body and legs as the woman hauls the rope, hand over hand. A second red vest crouches behind her.

“When you get close, we’ll each take one of your shoulders and haul you in,” the woman says.

My fuzzy brain tries to remember why that’s not a good idea.

It can’t.

And then it does.

The words come out in a long stutter. “I’m half naked.”

“You’ll be fine, dear,” the woman says in a way that lets me know she doesn’t understand.

I try again. “I’m bare-assed,” I yell.

My rescuers keep pulling. I don’t want the two of them to see me this way, but am too tired to worry. I offer faint kicks that propel me forward. My lifebuoy nudges the edge of the raft. I curl my elbows over the side and hang into the water to hide my bare bottom.

Heavy gloves grip my armpits and lift-drag me onto the rubber floor, with my head facing dirty gray rubber and my feet dangling over the water. October air ices my bare skin. Something fuzzy and warm wraps around my backside.

“We need to get you out of that wet top,” the woman says.

“But—”

She doesn’t let me finish. “Don’t worry. I’ll keep you covered.”

Her helper makes a teepee from one of the blankets and rolls me into a sitting position. Then, she pulls off my pyjama top and enfolds me in another warm cover. I’m cozy on the outside but shivery inside—like a baked Alaska with its ice cream centre and warm meringue coating.

I fade in and out as the woman and man steadily paddle toward shore. Both wear jackets so bright that I can tell where they are, even in the dark. Shadowy figures wait on the beach.

“Brandi, are you okay?” Dawn asks as we land.

I nod, too tired to speak.

“I was so worried.”

Tears gush from my eyes. “If it weren’t for you—”

Dawn hovers nearby as a tall paramedic with a bushy moustache approaches. “Does she need a stretcher?” he asks.