©®| All rights to the content of this journal remain with WordCity Literary Journal and its contributing artists.

Table of Contents

Letter from the Editor. Darcie Friesen Hossack

For this issue, we asked writers to delve into The Right to Read.

For writers, this right is also, inextricably, linked to the right to write. And this, with the right to safely, and with dignity, enter spaces that exist to promote our written words.

I know that am fortunate to live in Canada. To be able to write about difficult, even controversial subjects, without my government getting to have a say in whether my books are either published or burned. I am fortunate because most of my fellow citizens agree this should be so. And I am fortunate because, in too many other places in the world, just putting pen to paper can be a subversive, dangerous act. Danger, magnified exponentially by each and any number of layers of political and societal prejudice, by draconian policies and laws (see: Florida) and the associated threats of verbal and physical violence that may be meted out by governments intent on maintaining a status quo of inequalities.

But governments are not the only issue.

I cannot speak from any experience but my own. So in this space, I am going to speak from the experience of being a woman in what is still a jealously patriarchal world. I am white woman, to be sure, which comes with privileges of its own. But also with one glaring, persistent, often terrifying disadvantage in a world (both in Canada and abroad) where the gates are still being guarded by (*not all*) men.

Not All Men™

Not all. Just, for example, the TheoBros over at The New Evangelicals. A place that was the closest I’d come to attending church in more than a decade. The New Evangelicals, who in the last several days, made the decision to ban dozens of women from their Facebook platform for the sin of objecting to TNE’s presence at the soon-coming Theology Beer Camp (aka: “White Bro Summer”), after the camp decided to platform a known, narcissistic, domestic abuser and theologizer of “spiritual wives” as a workaround to marital infidelity.

Thanks to the work of many, many Jezebels, TNE’s presence there will not be a comfortable one. But TNE and other white men in power have made it clear that there are still no safe spaces for anyone but them.

And then, at the same time of my own banning from The New (Same Old) Evangelicals, came a certain TV interviewer. An interviewer who scheduled me to talk about my work, on air, before I had even agreed to appear.

In a pre-interview conversation, this educated, erudite man soon veered from the literary, into my reproductive choices (Had I definitively ruled out having children? How could I possibly say such a thing?), my appearance (“You look splendid, dear Darcie…dazzling”) and a request regarding my appearance on the day of our then-upcoming television appearance (“Could you not wear your glasses so you can look more dazzling and less like a nerd?”). And my favourite: “Your entire WordCity editorial board is made up of women? Is it a cult?”

This man, who held the gate to an international literary audience, then also asked why so many people in North America hate Donald Trump (on which point, I was glad to elaborate), and by the end, expressed a by-then predictable disdain and disappointment for the fact of my having included an LGBTQ+ character in my most recent novel, Stillwater.

I cancelled my appearance.

But? Why not stay and be part of the change and push back on air?

First, I would not be the one driving the course of the on-air conversation. And second, because the right to being taken seriously, as a full human being, in a space where others are respected both in front of and behind the camera, is not negotiable.

Which brings me back to the right to write including the right to safely exist in promotional spaces being as important as it is to being published at all. It is as essential as a writer’s right to not be banned by governments, schools. Or, as I once found myself, too, banned by a public library directed by a religiously conservative board.

It is this right to write, for storytellers and poets and truth-tellers to have their voices heard, that drives us to keep here working on WordCity Literary Journal. This mission won’t go on forever, but it will go on for now and for a time to come. Because, in this space, we aim to provide a platform for writers who are telling stories at the various margins of our societies. And that is something we all agree is worth our collective time and talent.

And on that note, we especially want to honour and give our gratitude to a particular group of poets who have joined us for this issue. A group whose courage we hope to continually work to deserve, for as long as we create this space. Our featured contributors: Trans Women Poets from the League of Canadian Poets, beginning with Rebecca Gawain.

Rewriting Feminisms:

Trans Women Poets from the League of Canadian Poets

Rebecca Gawain

(photo unavailable)

***

I hope when she looks at me

Glint of recognition in her eyes

She doesn’t bring it up

We don’t have to talk about the terrors

Our shared dating pools

Who hates us most

I don’t want to know your twitter handle

I don’t want to go to your potluck

Don’t tell me about scramz or hyper pop

I hate that Swedish shark

***

Time does not pass

Between December and December next

I still see you with the gleam of sun in your Eye

Boots against the ice, fur trim of your coat

I’m sorry I didn’t make it back from Christmas

That I weighed my organs this Easter against my sins

And was found wanting

***

Set a table for three

Leave an empty chair for memories

Yours, not mine

You absolve yourself with gifts

Time an arrow forward

Present me like a grotesquerie to your

Cousins, god parents…

Your new girlfriend mocks you

She speaks in hushed suggestions

You’re paying the bill

Anyway

Continue to Collection

Fiction. edited by Sylvia Petter

This fiction issue begins with a story by Jen Ippensen, Three Things You Should Know About Jarod J Brinkley III. In keeping with the times, there’s an element of “comeuppance”.

Then there is a flash by Cheryl Snell, allowing for Multiple Choice.

The havoc invisible illness can wreak is addressed subtly in Danila Botha’s story, There’s Something I’ve Been Meaning to Say to You.

Dave Nash’s flash, That’s My Baby in The Echo Chamber lets us see the hope invested in caring for an autistic child.

Finally, Rachel Fenton’s flash Words Written on a Thrown Vase is about truth, lies and the betrayal of confidences, alluding to much darker happenings.

Jen Ippensen

Three Things You Should Know About Jarod J. Brinkley III

after Lindsay Hunter

CW: Sexual Assault

One. Jarod J. Brinkley III has a 6th grade spelling bee trophy on a shelf above the desk in his private room at the Quads on campus at Wesleyan, his first choice of private schools where, because his father and his father’s father are alumni of the college, he enjoys a few minor perks as a legacy student, like a gold-plated lapel pin and early access to the dining hall on Sundays and several long-term members of the administration addressing him as Bud or Buddy or Old Chap or making time in their busy schedules when he needs a favor, like that time he missed the drop/add deadline and wanted out of Trigonometry to avoid a failing grade on his transcript. Of course no one at Wesleyan knows it’s an old spelling bee trophy. Jarod J. Brinkley III pried the brass name plate off the base years ago.

Continue Reading

Cheryl Snell

Multiple Choice

A novel/short story/ poem are lost in a library. A student/scholar/amateur rescues them and checks them out, but will not share with her classmates/professors/ habitués of coffee shops. They upend/shake out /Heimlich her newfound knowledge from her, but find she has already eaten/swallowed/assimilated it. The knowledge is her, she is the knowledge. They ambush her anyway, brandishing weapons/ placards/ backwards caps. Suddenly, a jackfruit/fig/mulberry tree breaks through the concrete. The trunk grabs/saves/protects the girl. The tree enfolds her, she inhabits the tree, the tree is she. Authorities decide she is a thief/sociopath/fraudster. They try to prune/ transplant/ cut her down, but her roots have caught them by their ankles and aerated/delved/turned them over into the soil.

Continue Reading

Danila Botha

There’s Something I’ve Been Meaning to Say To You

“I just laughed, what else could I do? And her friend chimed in singing get a clue/

Get a life, put it in your song/ There’s something I’ve been meaning to say to you…”

~Brendan Benson, Metarie

I wrote my first message and displayed it in my kitchen window, which anyone passing my ground floor apartment could see easily. It was a long sign, in black pen, in my sloping handwritten script, and it was a huge contrast to all the people who’d colorfully thanked first responders in the first wave and never bothered to take their signs down.

There’s something I’ve been meaning to say to you. Sometimes I miss the things we used to do together. Going to farmer’s markets full of local craftspeople selling overpriced infinity scarves and handmade moisturizer made in someone’s bathroom that smelled vaguely of lemongrass and lavender, that you insisted on buying for me. I miss the vegan organic restaurants you’d drag me to that I thought would be terrible, but often weren’t. I miss you taking me for walks on Woodbine beach, where that’s all we did. I miss you taking me to Fringe festival plays that I didn’t think were funny, or music showcases where you complained that the guitarist’s E string was flat, and I nodded like I understood what you meant. I miss watching you eat deep fried shrimp and fries while you never gained a pound. I miss going to Kensington and spending our last five dollars and change for something we’d never end up wearing from Courage My Love. I miss secretly reading your diary, where you were freer and more confident than you ever were in real life. I miss watching you show off gold jewelry your boyfriend bought you, so proud I’d almost forget that he’d cheated on you.

Continue Reading

Dave Nash

That’s My Baby in the Echo Chamber

No. We didn’t pay extra so he could yell the whole plane ride down from Newark to Orlando. We never ceased to be horrified and embarrassed and concerned for him. Since you don’t want to believe me, I’ll tell you a corroborating story.

I was walking him yesterday because that’s the only thing that works. And there’s this traffic light. We’re used to people being distracted because of cell phones and not seeing the light when it changes so we might think it’s a good idea to honk.

It’s not.

A three-hundred-pound woman got out of the car. She yelled that she was on her way home from her mother’s funeral. And she hadn’t spoken to her mom in five years. And now she was dead and so not talking. This lady who must have had a Derringer in her glove compartment because she’d been robbed too many times laid into the honking dude. Then she got back in the car, waited for the light to turn red and took that left.

Continue Reading

Rachel J Fenton

Words Written on a Thrown Vase

Teen was a word still used to describe her when you met her at the university library, your place of work. Teen is the word that describes the number of years you are older than her. I called you a predator when I worked that out, but you disagreed because you said she’d already fucked a man who was older than you were at the time. You didn’t say if he had children too. You didn’t agree with my assertion that being fucked by a man who was older than you when she was younger than she was when she met you only made her a victim of two predators.

Continue Reading

Non-Fiction. Edited by Olga Stein

Non-Fiction: Editor’s note on Censorship and its Erasures

Our Summer 2023 issue is finally here, and I, along with all of our editors, wish to thank contributors and readers for their continuing interest and patience. The theme of censorship is an important one, as the news reaching us daily from the United States and Russia makes evident. In both countries, those with the most power want to control history as it unfolds, as it’s recorded, and as it’s recounted. Those who control history, shape society and politics of the present, and its forms in the future. Censorship is therefore a crucial tool for those who hope to maintain such control. In the US, current efforts to censor books and school lessons pertain to historical facts/truths about the capture and enslavement of people from the African continent, and the subsequent oppression of former slaves and their American-born descendants. In Eastern Europe, censorship entails the execrable attempt by Russia to justify its invasion of Ukraine, a sovereign nation. Russia is aiming for nothing less than the erasure of Ukraine as a nation, while eliminating any and all voices who oppose this blatant and brute imperialism.

Russia has always been authoritarian. Its authoritarianism has waxed and waned over the centuries (depending on who controlled the state apparatus), but censorship was always part of the incumbent regime’s playbook. Still, until now, nothing could compare—in degree and scope of iniquity—with Stalin’s regime, and Stalinism as political strategy to maintain total authority by wiping out all dissent, all differences of opinion and approach, in every sphere of professional and private life.

…

Nina Kossman’s elegiac memoir, “Lysenko, Enemy of Soviet Science, and a Dissertation Left on a Windowsill,” is a testament to the pernicious effects of censorship in science during Stalin’s era. Soviet biologist Trofim Lysenko waged war on Mendelian genetics and science-based agricultural techniques (denouncing them as bourgeois pseudoscience or imperialist genetics), which resulted in the dismissal, imprisonment, or death of thousands of mainstream biologists.

Continue Reading

Nina Kossman

Lysenko, Enemy of Soviet Science, and a Dissertation Left on a Windowsill

In memory of my mother, Maya Borisovna Shternberg

Back in the seventies, people emigrating from the Soviet Union were not allowed to take with them certain things, such as books published before 1917 (the year of the Bolshevik revolution), manuscripts, typescripts, works of art, and so on. Since the Soviet Union did not have diplomatic relations with Israel, and 99% of hopeful emigrants were going to Israel, the only country to which it was possible to apply for permission to emigrate in those years, the way to take forbidden items out of the USSR was to give them to a Dutch Consul, who would return the items to their owners once they were outside the Soviet Union—i.e., in Israel. There was, however, a limit to how many items prospective emigrants were allowed to give to the Dutch Consul.

My parents wanted to give my mother’s academic dissertation to the Consul, but I said I would not leave without my watercolors, and since even children’s pictures had been classified as “art” by the state apparatus, my parents had to choose between my watercolors and my mother’s dissertation. They were loving parents, and they decided in favor of my watercolors. This was how, and why, on the day we left the Soviet Union forever, a cardboard box with my mother’s dissertation remained on a windowsill of our empty apartment, next to a smaller cardboard box with my father’s WWII medals. It doesn’t take much imagination to visualize the contents of both boxes—the dissertation and the medals. These were treated like garbage by those who moved into our apartment after we had left. I know for a fact that my father never regretted leaving his war medals on that window sill. He had never shown them to us anyway, except once, when I asked him to, and he took them out of the box for just a second, saying that it’s nothing to be proud of, and that being a soldier in the war that had killed millions, including most of his family, was not a matter of pride or wearing medals, like so many believe, but of grim necessity. As for my mother’s dissertation, this was a different matter; I have no doubt that my mother regretted leaving it.

Continue Reading

Poets in Translation by Philip Nikolayev

Philip Nikolayev is a poet living in Boston. He translates poetry from several languages and is currently translating poetry from Ukraine. Nikolayev’s works are published internationally, including such periodicals as Poetry, The Paris Review, Harvard Review, and Grand Street. His several collections of verse include Monkey Time (Wave Books; winner of the 2001 Verse Prize) and Letters from Aldenderry (Salt). He is coeditor-in-chief of Fulcrum: An Anthology of Poetry and Aesthetics.

Arkady Shtypel, translated from the Ukrainian by Philip Nikolayev

Arkadiy Shtypel is a Russian Ukrainian bilingual poet, translator, and author of several works on poetry. He was born in 1944 in the Uzbek city of Kattakurgan during the WWII evacuation. His childhood and youth were spent in Dnipro, Ukraine, where he studied physics. He was expelled from his university for attempting to create a samizdat literary journal, and was at the same time accused of both Zionism and Ukrainian nationalism. After military service, he completed his university studies via correspondence but never pursued a career in physics. In 1969, he moved to Moscow and published several volumes of poetry. His first collection, Visiting Euclid, saw the light of day in 2002. In 2016, a book of Shtypel’s translations of classic Russian poetry into Ukrainian was published in Kyiv by the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy Publishing House. He has been a regular participant in the Kyiv Laurels literary festival and in the poetic programs of the Lviv Publishers’ Forum. He has been residing in Odessa, Ukraine, since 2021.

Continue to poets in translation

Olga Stein

Mikhail Iossel’s Love Like Water, Love Like Fire: The Soviet Jew in Full Colour

Mikhail Iossel’s collection of memoir and lyrical pieces, Love Like Water, Love Like Fire, bears witness to a particular kind of experience — that of living and identifying as a Jew in the Soviet Union (now former Soviet Union) during the 20th Century. To be more precise, the majority of these autobiographical stories deal with Iossel’s own past before 1986, which is when he immigrated to the USA. Highly literary and genre-blending, they serve up a kind of anti-paean to a life Iossel left behind in a country and part of the world whose ideological fashioning differs vastly from the one we’ve been socialized in as Westerners. As these stories suggest, the Soviet-era world is so utterly unlike ours, so prosaic and unsettling at once, that literature aiming to convey this strangeness requires its own narrative strategies. In Love Like Water, Love Like Fire, characters and situations are more the stuff of phantasmagoria than memoir or “realistic” autofiction. Yet Iossel’s artistry is such that anyone born and raised in this country and its paranoia-inducing regime, any reader with an understanding of its mind-numbing, grim totality, would think these stories, their content and form, not just apt, but true to life.

As a whole, the collection testifies to Iossel’s keen sensibility and unmistakable erudition. There are moments of sly and overt intertextuality, and unmistakable literary panache. One piece, simply titled “Sentence,” and dedicated to the writer and language poet Arcadii Dragomoshchenko, unfolds as an interior monologue in, to be sure, a single sentence. It recalls an semi-illicit gathering of dissident writers in an otherwise empty building in a central part of Leningrad (St. Petersburg since 1991). This piece gives expression to different registers of emotion; part nostalgia and elegy for a bygone youth in a resplendent metropolis, known the world over as “Venice of the North,” it nevertheless homes in on the narrator’s awareness of and anxiety elicited by the city’s governing ethos and of the country as whole.

Continue Reading

Literary Spotlight with Sue Burge: Gail Anderson Dargatz

![The Almost Widow: A Novel by [Gail Anderson-Dargatz]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51obadq-JAL.jpg)

For this issue I am delighted to meet Canadian writer Gail Anderson-Dargatz. I’m not sure if there is a genre she hasn’t written in!

Gail, you are an extremely successful and experienced writer, working across most genres: poetry, short stories, novels and YA fiction. Within these genres you tackle everything from thrillers to historical dramas, all with gorgeously engaging titles. The Cure for Death by Lightning, your first novel, really shows your eclectic approach. It’s a coming-of-age story set in rural British Columbia during WWII that features magic realism elements and recipes throughout! I wondered what initially set you on the path to becoming a writer? Have you always written? When did you first think, “I’m a writer”?

My oldest sister tells me that when I was seven, I told her I wanted to be a writer. I even have a note written at the time to that effect. My sister was a writer, and my mother was a writer. More importantly, my parents were both big readers. I grew up in an environment where writing and reading were valued. So, I grew up writing. I just took it for granted as a pastime. I didn’t believe I could make a living at it (and I sometimes still don’t!) but I couldn’t think of anything I’d rather do. I bugged the editor of our local paper, The Salmon Arm Observer, to let me write stories in my teens, mostly about school stuff. Later I took a short journalism program and again bugged the editor of my local paper into hiring me as a cub reporter. During the time I worked there, I started sending my fiction stories out to literary magazines and contests. One of them won a competition judged by Jack Hodgins. He became my mentor as I entered the University of Victoria creative writing program. While there I continued to send stories out and one of them, pulled from a rough draft of The Cure for Death by Lightning, won the Canadian Broadcasting Company (CBC) short story competition. I met an agent at the gala who took me on and eventually sold the novel internationally, launching my career. It was something of a Cinderella story, as I was milking cows with my first husband at the time, but it was a Cinderella story that was ten years of work in the making.

Continue Reading

Books and Reviews. Edited by Geraldine Sinyuy

Lori D. Roadhouse reviews Debra Black’s

“love, lust, existence and other ephemeral things”

I read these poems first in order, then backwards, and also randomly. Each poem exists on its own merit, as a breath in time. The breaths come faster, or more slowly, depending on the subject matter, and depending on the order in which they are read. It’s almost a meditation, a rocking chair, representing the rhythms of life.

This, in the middle of a love poem, as the subject imagines making love with both Pablo Neruda and her real lover, Death. The poem begins with caresses of tender words, rises to a quickening and climax, then resolves back into wistful tenderness. Languid, gentle breaths in nature morph into panting, lusty inhalations of sexual fantasy and physical exertions. The ever-changing tidal motion in this book is at times comforting, at other times perplexing, often very sensual and unapologetically sexual.

Continue Reading

Sweating and Reading.

an essay of books by Gordon Phinn

Books Referenced:

Into the Soul of the World, Brad Wetzler (Hachette Books 2023)

The Man Who Hacked the World, Alex Cody Foster (Turner Publishing 2022)

Still Pictures, Janet Malcolm (Farrar, Straus & Giroux 2023)

Ghosts of the Orphanage, Christine Keneally (Public Affairs 2023)

We Were Once a Family, Roxanna Asgarian (Farrar, Straus & Giroux 2023)

Just Once, No More, Charles Foran (Knopf Canada 2023)

Strange Bewildering Time, Mark Abley (Anansi 2023)

Tautou, Kotuku Titihuia Nutall (Anansi 2023)

Darke Passion, Rosanna Leo (Totally Bound 2023)

Lost Dogs, Lucie Page (Cormorant Books 2023)

Duck Eats Yeast, Quacks, Explodes, Gary Barwin & Lillian Necakov (Guernica 2023)

Seeing the Experiment Changes It All, Dale Winslow (NeoPoiesis Press 2021)

Surface Tension, Derek Beaulieu (Coach House 2022)

The Garden, A.L.Moritz (Gordon Hill Press 2021)

As Far As You Know, A.L.Moritz (Anansi 2020)

*

Imagine Brad Wetzler graduating and quickly finding an internship at a nationally famous magazine and within months moving up through the ranks to an editorial position which gave him easy access to famous adventure travel writers, many of whom he held in great regard, and gradually realizing his secret ambition to be an adventure travel writer himself, pitching ideas here and there, getting the green light, fulfilling his ambitious plans and publishing in Outside, George and the New York Times, pulling in six figures per annum while enjoying a fruitful partnership with a lovely and talented editor in the rarified air of Sante Fe, New Mexico. Just imagine: it all seemed like living the dream and it was, as long as he ignored the wounded child, lousy self esteem hidden inside his welcoming smiles and soulful camaraderie shared with colleagues and friends. Ah yes, wouldn’t you know it, the culprit was that poisoned chalice of the nuclear family in which a few manage to swim, flotation devices attached, but many fail to survive.

All clichés of the modern autobiography, the memoir with those gaping wounds of the psyche that always, in the end, have to be attended to if depression, drugs and romancing suicide are to be skipped rather than surrendered to. A familiar tale of woe, and if the author is not careful, a hefty dose of woe-is-me. And with Wetzler I’m afraid the latter is the case. One does not require the details of every insult, slight, defeat and failure to see how he failed to settle the scores necessary for survival. He repeatedly seeks approval instead of demanding the respect that psychotic families will never give.

Continue Reading

From Spagin (Lecce, Italy). a review by Marcello Buttazzo. translated from the Italian by Bruce Hunter

From Spagin (Lecce, Italy) by Marcello Buttazzo. Translated from the Italian by Bruce Hunter.

Bruce Hunter is a great Canadian poet and writer. In 2022 his book A Life in Poetry (based on his Two O’clock Creek- poems new and selected) was published in Italy. Bruce was deafened as a child and suffered from low vision for much of his adult life. He grew up in Calgary, in working-class Ogden, in the shadow of Esso’s Imperial Oil refinery. After high school, he worked as a laborer, equipment operator, Zamboni driver, gardener, and arborist.

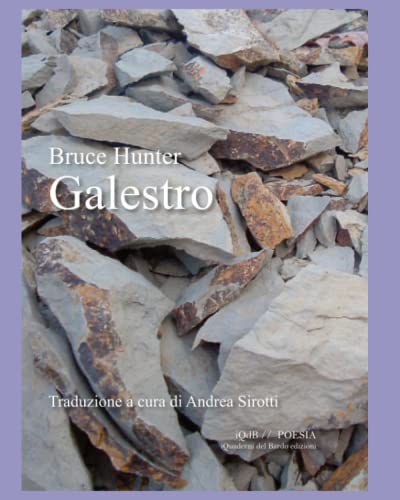

In his late twenties, his poems earned him a scholarship to the Banff School of Fine Arts. His poetry, fiction and creative essays have appeared in over 80 international blogs, magazines and anthologies in Italy, Canada, China, India, Romania, the United Kingdom, the United States. Among the various awards we remember, in 2010, the Acorn – Plantos Peoples’ Poetry Award for Canada. Bruce Hunter is a life member of the Canadian Hard of Hearing Association (C.H.H.A.) and the Canadian National Institute for the Blind (C.N.I.B.). Recently, in February 2023, a book of his verses entitled Galestro was released for the Quaderno del Bardo editions.

The title of the volume is emblematic. Galestro is a sandy soil, rich in minerals, found in the Chianti vineyards in Tuscany, where Bruce Hunter made a meditative journey. We humans are children of the stars. We are products of the collapsing stars; we are made of their stuff. As Carl Sagan writes, “the nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood, the carbon in our apple pies were produced inside collapsing stars.”

Continue Reading

Poetry. Edited by Clara Burghelea

Fabrice B. Poussin

Trail conversations “How you doin’? she asks not waiting for the conformist answer too busy taking a sip of her holy water wrapped in plastic and early morning dew. “Good mornin’!” they claim in bright accents from North to South and other climes boasting those ivory smiles as if tomorrow would never come. “Have a good day!,” the gentleman softly speaks in the path of a wife of fifty years but she seems more interested in this lonely sight as I snap another memorable landscape with a superzoom. Voices echo as if words were spoken centuries before in my head as they shake my achy muscles ignorant of my inner thoughts, friends for a moment and soon I ceased to exist for the chance encounters of these elusive friends. It is an odd realization, albeit for a mere second to feel human in the midst of a universe that does not care too much whether they think you good or bad.

Continue to 2 more poems

Geraldine Sinyuy

Plant a tree Walk today with those who will walk with you, Should they leave you half the way, Plant a tree for them and mark the day, So that if ever the road leads them back to you again, you'll have at least a shelter to offer if not a fruit. Walk on and as many as part ways with you Keep planting trees So that every embarrassment becomes a tree

Continue Reading

Mansour Noorbakhsh

Sometimes ponder why the sky looks blue You force me to read your books. As you warn me from reading others. I’m wondering have you ever looked at the sky, at the bushes on your way, or at the sand and soil. Look at everything again. Sometimes stand under the rain till it washes your whole body including your eyes. Then maybe you will realize that what you force me to read and believe has been considered forbidden words somedays. Those days that your ancestors were killed for reading forbidden words and believing them. Sometimes sit next to a stream and stare carefully into the water that reflects your face. And your eyes too. Maybe you will realize thus, you look more like the murderers of your ancestors than the ancestors whom you inherited your faith from. Sometimes trust yourself and ask why the sky looks blue.

Continue to 3 more poems

Catherine Zickgraf

Violining Gusts blow wild sky off its clothes line, and fog soaks into my coat. I lift the gate latch, enter under a canopy of greens and into the courtyard. I stay this January in Carmen de la Victoria, the stone and oak guest house of the Universidad de Granada. Halfway up the river valley, I come home to the ghosts of former guests. I’m comfy now in a dry sweater. The ladies feed me fish soup and red wine. This pale afternoon I settle into the dining room, facing windows that gaze down the hill.

Continue Reading

Jameson (Jason) Chee-Hing

The World Is Not Right The world is not right when It is not just Do not forget us we have no voice tell the world about us the voiceless...the enslaved...the displaced…the imprisoned To the poets and writers do not forget us give words to our plight tell the world We are in the re-education camps forced to renounce our faith...our birthright…re-educated we are in the nameless prisons we dared to speak out dared to want want what you take for granted our basic rights We are the displaced violently removed from our ancestral lands because we look different we have no voice we are the forgotten souls I am now a number recorded in some book the list of the forgotten buried under my native soil in the deep woods no marker for my loved ones they have only their memories now The world is not right when it is not just.

Continue to 1 more poem

Lela Hannah

Fractured I. Childhood I’ve tried too many times to wedge myself into an electric socket, an Alice in Unwonderland, insisting on existing in places that can never accommodate me. II. Adolescence Multi-talented is defined by being able to cry and eat ice cream without swallowing tears. III. Adulthood I make glass figurines seal the cracks with the stickiness of my blood.

Continue to 1 more poem

John Brantingham

On the Edge of the Marsh Ginny and her husband have a farm here at the edge of the marsh, a place my grandfather, a dairyman all his life would have felt at home. They have cows and grow corn, strawberries and asparagus, and they listen to great blue herons grawking to each other across the water. I hear them too as I buy cucumbers from Ginny’s cart, and I hear my grandfather, dead now 60 years, talking and laughing. The two of them speak of things beyond my understanding, They speak the language of peace, the language of things that make sense.

Continue to 2 more poems

Marc Isaac Potter

Time Pairs of little bare feet Running across the Kentucky Bluegrass, Children laugh as they run, Showing off their new Easter clothes. Pappa pops a beer In the hot pool and chugs this one too. Momma is in the house Peeling carrots while Auntie Cleans in another part of the house. All is being readied For the disaster.

Continue to 2 more poems

Sabyasachi Nazrul

Oh Lord... Oh Lord... I have cultivated paddy in your land. I have also cultivated onion, garlic, ginger and tomatoes in another land. I cultivated fish in the pond and gourds in entresol by the pond. Good yield, I got good paddy in the field. I packed one years worth of paddy to eat with my family and sold fifty mounds. I am well in Your mercy. Oh Lord... there is no shortage, O Allah guide me to the path of light. I drink your water to cool my soul. I walk through the valley alone in the dark. I fear no evil.. I'm not alone,

Continue Reading

Carl Scharwath

Telos Two evening lovers’ echoes In you forgotten dreams And memories of essence. Touch wordlessly in a greater optimism. Waves of summer morn Under a cloudless sky With flickering lights of desire. Turning like a dancer alone on the stage of life The collapsing leaves turn After their first death and sleep In the place of forgotten Gods.

Continue to 2 more poems

Susmit Panda

If only I could set things straight, I might.

But I am spent! I miss my family.

Has brother left the building for the night?

The sink is chockablock, the TV’s bright

And muted, roaches raid the cutlery.

If only I could set things straight, I might.

Isn’t it time? The far-ranked bulbs that light

The dirty steps will blink out suddenly.

Has brother left the building for the night?

I might, in darkness inching down the flight

Of steps, trip on somebody, till I cry:

If only I could set things straight, I might.

The crescent moon is aging in plain sight.

The pickets wrap back into obscurity

—If only I could set things straight, I might.

O brother, have you left us for the night?