How to Mother a Woman

My daughter became a woman on a Thursday. I was just finishing my first semester teaching at a local college, busy giving last lectures and frantically marking student papers. Many of my students, overly vocal about their marks, were emailing me several times a day before their grades were finalized. Everything felt urgent.

For several years I had imagined this day. I thought that somehow, from my own inner resources, I would spearhead this transition. I envisioned an eclectic mix of red tent and tradition. I imagined friends and family offering their wisdom and perspective. I imagined women gathering. But when my daughter let me know it was time, my first thoughts were how inconvenient. I knew we were supposed to pause for ceremony for four days, and frankly, I didn’t have the time or inclination to do so.

Did I mention she became a woman during a pandemic?

Did I mention we were all living with my ex-husband at the time? It was something I swore I’d never do again, but when we found ourselves in between places it became necessary. We were family after all, and in the disruption of the pandemic, coming together as a family felt like a relief. Actually, it had been a fine two months. All of us had managed to get along. But the girls and I were only a week away from getting the keys to our new place. Didn’t my daughter’s body know that we were right at the cusp of a move and a new life?

If it had happened a week from now, I told myself, I’d be in control. Things would be rolling out in my house. Being at my ex’s house meant that I didn’t feel completely free to run things my way. Actually, I didn’t feel that I was able to run them at all. In addition, the pandemic was new; rules, restrictions, and people’s own sense of safety had kicked in, and I was hesitant to invite people other than family over.

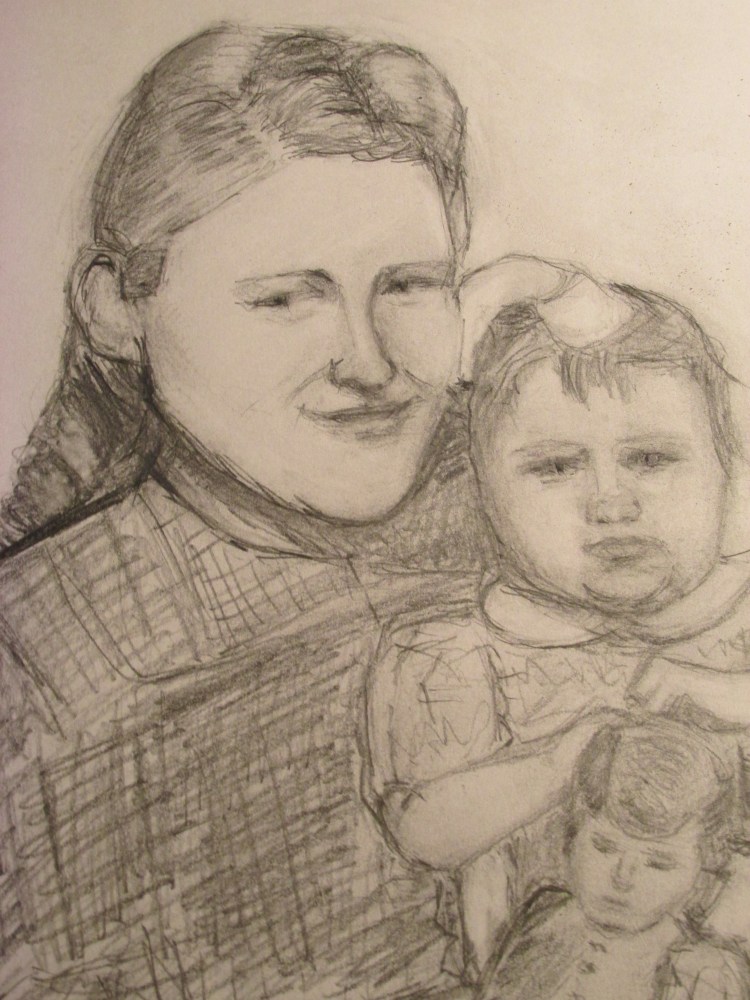

I called my ex to inform him about the turn of events, only half-knowing what it meant for us. Within an hour, my mother-in-law and two of my sisters-in-law were at the house. They brought all the necessary supplies and made sure my daughter was going to be prepared for this time. I became a bystander. I watched as my girl’s hair was braided, and I listened as her aunties told stories. A sewing machine and small desk were installed in her room. I let my mother-in-law take over. Thankfully, she was open to a modern interpretation of what the next few days would look like.

My daughter was overwhelmed. She needs her own space on the best of days, and as I watched her trying to take in her aunt’s stories, along with the rules she had to follow for the next few days, I saw her reduced to tears. Technically, tears weren’t allowed. I gently escorted the aunties out.

I listened to the instructions directed at me—things about cooking, cleaning, and sewing. We would have a feast on the final day, and thankfully most of the food preparation would be looked after. I listened to the expectations, many of which I thought were archaic, and I felt mad. I was angry at this disruption in my life and the poor timing of it all. I felt as if I was in some foreign country. I wanted to embrace this ceremony, these teachings, and the whole process, yet I found myself seething with anger.

Didn’t everyone know that I was a fucking college professor? Okay, a sessional professor, really a one-session professor. But still. I was too important to do “women’s work,” and wasn’t women’s work well beyond washing the floor? Shouldn’t we protest or do something else that is meaningful?

I also felt territorial over my daughter. If anyone was prepared to guide her into womanhood it was me. But I had no knowledge of this ceremony and I wanted to honour it.

On day one I was largely recalcitrant. I had things to do and I refused to disrupt my life. I told my ex-husband that this was inconvenient for me, and he reminded me that ceremony, especially this one, was not observed for my convenience.

On day two I stewed in my own anger as I answered emails from whiney, undeserving students, asking for their marks to be increased.

On day three, I shut my computer off, and I shut my work down. I informed my students that I was unavailable, and I committed half-heartedly to the ceremony. I started cooking and cleaning in preparation for the feast on day four. Also, I got curious about my anger. Instead of telling myself to feel better or to do better, I just let it be. I wondered why I was so angry.

I reflected on my own coming of age—at how little fanfare there was. It was the summer before grade eight. We had been camping that week, and I had spent the day boating, tubing, and learning how to kneeboard. It was a day I had enjoyed thoroughly. When we got back to our trailer, I made the discovery as I changed out of my swimsuit.

Fuck, there is blood in my swimsuit. I had waited for this moment, compared stories with friends. I had desperately wanted to be a part of this club. And here it was: dark blood stains on my swimsuit. All of a sudden, I didn’t want this anymore.

But there was no denying it. I was a woman. I felt a shift. I was actually scared of disappointing my dad. I was never overly girly; I think I had tried to hide any form of femininity from him. Maybe, I had hoped that he would like me more, but at that moment there was no denying that I was a woman. I felt disappointed—in myself, my body, the whole process.

I let my mom know. Maybe I cried. I don’t remember.

When I stepped out of the trailer, my dad said, “Sounds like we need to buy some kotex.”

I was mortified and betrayed all at once. How could my mother tell him?!

And here I am now with my own daughter, and we’ve told the whole family. And it’s a really big deal. My mother-in-law comes by every day to check on things. My daughter is following half of the rules. She’s on her phone and computer, though I do ask her to maybe hide the evidence when her kokum comes over. She won’t keep her hair in braids either, and she keeps crying. I can see the defiance in her.

I try to remind her that someday she will reflect on this time and be grateful. She just can’t see it yet. I also give her a lot of space.

I hunker down to clean the house. Did I mention my ex’s house is clutter central and I hate cleaning there? I simmer in my own anger as I cook a lasagna, my girl’s favourite, for the feast.

My ex has told me many times to relax, but my anger radiates towards him as well, as he has largely been off the hook for this entire thing. He was told to stay out of the house. I think about how easy it is for him to tell me to chill when I’m expected to do my share of the women’s work. I have a dress to sew, food to cook, and giveaway items to prepare.

My anger wont simmer down. Instead, it keeps growing and it’s out of proportion with what’s being asked of me. My mother-in-law has been nothing but gracious. And, after all, I’ve hosted dinners that I didn’t want to host. I’ve done things out of a sense of duty, but for some reason my anger won’t stop. I continue to wonder about this. Why am I so fucking angry?

Here’s what I won’t admit about cleaning and cooking. Sometimes, when I clean it’s like meditation. I don’t know why, but as I sweep the floor or wash dishes, I feel inspired. It somehow opens up a channel for Divine inspiration, and I am able to—clear as day—receive some sort of guidance.

On day three, somewhere between getting the lasagna in the oven, scrubbing the toilets, and sewing a ribbon skirt for my younger daughter, I sense a shift. In the quiet of this “women’s work” my anger starts to make sense. I’m not mad about cleaning. I’m not mad at my mother-in-law, or my sisters-in-law, or my daughter, or even my ex-husband.

This anger I feel, it’s like an awakening. I start to reflect on what this ceremony means for me. What does it mean to be the mother of a woman? My early motherhood days have passed, my role is changing, and I wonder if I’m ready to take it on.

As I reflect on how I can be a mother to a young woman, I realize that this ceremony, this time is calling me deeper into my own womanhood. It’s calling me to stand more firmly in my own power—in my own knowing. Being a mother to a woman is a transformation for me as well.

This anger, this angst I feel, is perhaps one part worry and one part an awakening. I am embracing myself in new ways. Deeper ways. I am embracing my own knowledge. I am embracing my own path. I am embracing my own deep desires as a woman. I am being called on to move into this next phase of my life and I can feel it. It’s palpable. How do I mother a woman?

Rising. I am a mother to a woman now and my own womanhood is calling to me, telling me to go deeper.

My anger was masking my own discomfort—my own call to personal transformation. I could have missed it completely. I could have complained about my mother-in-law, or about the ceremony, and how it failed to grasp modernity. I could have refused to do work I considered beneath me.

Instead, I sat, questioned, and got curious. It opened the door for new understanding. It opened the door to my new power. It opened the door to my own fears because I knew I wasn’t fully been living as a woman myself. Despite my marriage and the birth of my two children, I had missed some of the transition to my own womanhood. I had yet to fully embrace myself as a mother, and as a leader. I still played daughter and I knew this had to change. I knew that in order to fully embrace this role, this deeper role of motherhood, I had to relinquish my role as daughter. I had to release any expectations or roles that didn’t let me fully be me.

I had to stand fully present in the ever-changing landscape of the person I was, be a pillar for my own daughters, and witness their unfolding.

Being a mother to a woman was a deepening of my role. My daughter was no longer a girl, and neither was I.

On day four, several of our family members gathered in our living room for prayers and food. I watched as my daughter’s grandfather prayed for her. Openly. I watched as he embraced her. Openly. I watched as she was celebrated for the transition she had made. Openly. I listened as her grandfather explained to her that he had prayed every day for her for the past four days. He prayed for her wellbeing, prayed for her transition, prayed for her future.

I watched as she was embraced. I felt the prayers of every family member present, and of the ancestors who gathered to witness this moment. This was a historic moment right there in our living room.

I looked at the faces of every one of our family members. I watched as she was honoured by her aunties and her cousins. I watched in awe as she was celebrated.

No hiding, no shame. It was a celebration.

I watched as this kid I birthed was embraced by many. I felt love, support, and prayers surround all of us.

I didn’t cry until everyone left. And now still, as I write this, my tears flow in gratitude, and in awe. I feel the energy, the prayers, and the intent of that moment rise up to meet me.

I laugh at my own self; I had kicked and screamed, and rebelled like a child. I laugh at myself for thinking, when the time came, I would somehow know what to do, and then realizing that I needed support.

I am eternally grateful to the family that embraced me despite my marital status, to the teachings, and to old-school woman’s work, which gave me the space and quiet solitude to grow.

Teresa Callihoo is an Energy Healer and Storyteller living in Wetaskiwin, Alberta. My Dad is a member of the Michel Band and I feel grateful to live in Treaty 6 Territory. I believe sharing our stories helps us connect to one another, reflect on our experiences and write our next best chapter.