©®| All rights to the content of this journal remain with WordCity Literary Journal and its contributing artists.

On October 7th, Hamas terrorists breached the fence separating Gaza from Israel and tortured, raped, mutilated and murdered at least 1200 women, men and children.

1200 women, men and children. Dead. Before taking an estimated 240 others into captivity as hostages.

Israel’s far-right leaders soon responded to these atrocities with war, and after weeks of bombardment, 14,000 Gazan women, men and children lie dead, with even more injured.

14,000 women, men and children.

Children.

Babies.

Sons and daughters.

Kids who should be counting their toes. Playing on playgrounds. Sleeping in their parents’ arms. Whispering with their friends.

And while there is an agony of very real history that the world is now grappling to understand, there are also opposite truths that too many are failing to hold in the same space:

Terrorism has no justification, and war is an atrocity.

Israel has a right to defend itself, and Palestinian lives matter.

The use of human shields by Hamas is a war crime, and those being used as human shields deserve life and protection.

We can want the bombs to stop, and at the same time, for the captives to be set free.

We can, each one of us, be on the side of humanity.

And yet, around the globe, we are lining up on opposite sides of the street to hurl insults at one another. Hate crimes against Jewish people and Muslims have spiked. Pictures of missing Israelis are being torn down and the stories of Israel’s victims and survivors mocked, celebrated and dismissed by people on the right and the left. While at the same time, millions of Palestinians are being painted with the same murderous brush as Hamas.

At WordCity Literary Journal, we stand on the side of humanity. Of peace. And yet, we understand that it’s impossible to negotiate peace with terrorists who consider violence their birthright. Who, in their very charter, call for the destruction of their neighbours.

We do not have any answers among us. Just our humanity. And with all of our compassion and grief and hope, we believe that all who are innocent deserve life and security and hope. We also understand that those who act with evil now were not born that way. Because we also know that despair is a powerful recruiting tool for extremists.

As journal editors and writers, we don’t know how to achieve peace, only that peace is the only answer. So we stand, here in this space we’ve created, with the broken in body and spirit, with the hopeful and the hopeless, and with those who are working for a better way forward.

It is our hope that you, dear readers, will stand here with us.

Fiction. edited by Sylvia Petter

Sylvia Petter

A Fly in Amber

My mother had a large piece of amber the size of my hand. She held it up to the light and I saw an entrapped insect. An ordinary fly. My mother said the amber came from Eastern Germany, from the Harz Mountains where she’d lived before the war.

Darcie Friesen Hossack

Beet Roll (Chapter 2 of Stillwater)

Marie adjusted the waistband of her skirt, a consequence of Mrs. Schlant’s pancakes. Too much bran always made it tighten. So, for that matter, did Lizzy and Daniel whenever they disagreed. And since both of those things were true today—too much friction and too much fibre—it was difficult to know which to blame for the tightness that had begun to cinch her insides like the strings of a purse.

“How about we play a game while we drive?” Marie offered toward the backseat of the car, where Lizzy and Zach silently, if not patiently, passed the time. Both shook their heads and Marie turned back to face the road.

It had only been an hour or so since they had driven away from Stillwater. Already, though, daylight had become gritty and turned to dusk.

Without a word, Daniel switched on the headlights. They needed to be cleaned, Marie thought. Even on high beams, they barely spilled enough light for something to come into focus the moment it became too late to swerve. It could be a deer, Marie imagined. Or a rock the size of a chesterfield, slipped from an unstable bank. Or it could be one of those cheerless, soiled people who seemed, for no reason—thumbs in, they carried nothing—to drift between towns along the shoulder of the road.

Non-Fiction. Edited by Olga Stein

Bianca Lakoseljac

Excerpt from the Introduction to Rudy Wiebe: Essays on His Works

Why the collection, Rudy Wiebe: Essays on His Works? That is the question a number of my colleagues and friends asked when I talked about compiling and editing an anthology on Wiebe’s works.

During my graduate studies at York University, I took a course, “Special Topics: Frog Lake Massacre, 1885.” I read Rudy Wiebe’s novel, The Temptations of Big Bear, and found it transformative. My perspective on history, informed by so much—the Canadian colonial viewpoint; my inherited Eastern European history dominated by wars and continuous ethnic conflicts, which culminated in the breakup of Yugoslavia, the country of my birth and idyllic childhood; my family saga in Serbia which includes relations in Bosnia, Monte Negro, Croatia, among other regions; my personal life path which felt disconnected and discontented—all of that took on a different meaning. I began to look at life through a new lens; no longer did I see myself as a victim of circumstances, or wrong choices made, or unfortunate outcomes of providence. I turned to the “big picture,” to contemplate how other societies fared in this expansive, magnificent, wondrous, yet often astonishingly brutal world.

. . . . .

Rudy Wiebe: Essays on His Works examines Wiebe’s achievements as an author, editor, professor and mentor, who helped shape successful authors, gave rise to new approaches in the art of storytelling, and encouraged a passion for English Canadian Literature. The collection is a mosaic of critical essays, interviews, literary journal articles and reviews. It depicts the life and work of an author deeply involved with his Mennonite literary community, as well as with the English Canadian one, and who is among the most innovative, celebrated, and prolific. The main themes of Wiebe’s writing are bound up with his Mennonite heritage and his interest in Canada’s Indigenous past. The pieces featured in this collection are intended to create a conversation with one another, and to serve as witness to the changing times in English Canadian Literature.

A prelude to the collection is a witty and heartwarming cartoon, “Teaching Rudy to Dance … all true events,” by the iconic Canadian author Margaret Atwood. Rudy Wiebe’s comment that Atwood was trying to teach him to dance—“Classic ironic Peggy [Atwood’s name used by friends and family]. We’ve been friends since 1967”[i]—attests to this literary giant’s collegiality and good humour.

Mozid Mahmud

Jibanananda Das: Nationalism and Internationalism

Jibanananda Das had tried writing poetry in English, had written a few essays in the language too. But those did not go quite well and even when they did, it meant nothing for Bengali literature and its readers. He did not try being (in)famous the way Madhusudan Dutta did; Madhusudan Dutta had realized quite early on that it amounted to begging abroad. Having been a student of English literature and a teacher, Jibanananda had mastered the tongue of his Colonial overlords. His deep connections to English literature acted as a solid foundation for his later work in Bangla. It could be said that most of the authors who had helped Bengali literature to flourish in the beginning of the twentieth century were well acquainted with the English cannon.

Jibanananda Das, however, felt it was necessary to understand English in order to critique the poets and the literature. In his essay, “Desh, Kal O Kobita,” he had discussed this matter at length — that it was necessary to know English for the sake of Bengali poetry. But he did not believe that English poetry was the best of them all, of course. He thought that as it had spread in most parts of the world, and regardless of how it achieved it, it would act as a helpful vehicle, one that would help us become familiarized with the literature of the world in other languages. English, he thought, connected him to the greater world outside.

Brian Michael Barbeito

Sahasrara, Thousand Petaled Lotus

Prose Poem, Letters Home, Adventures in Creative Non-fiction

(a belles lettres epistolary episodic)

‘But we are all a bit broken, aren’t we?’

Maggie The Capricorn Woman.

Prologue: The Woodlands Whimsical and Wondrous, a Stone in my Shoe but the Fine Firmament Blue

I am atop the hill, on the summit, and in the distance a solitary deer passes. I can see just above the flaxen feral reeds, swaying spectres in the autumnal winds, as I am over six feet tall. Then the deer is gone. The canines didn’t see it thankfully, and we stand alone then. There is a small stone that has gotten into my shoe and use the time there to lift my left foot, balance on my right, and get it away by shaking it out and then putting the footwear back on. This happens in one motion. I don’t fall in the fall. The fall is my season, a season of creativity and even providence. I succeed. I still got it, as they say.

Tracey Keilly

The Hitchhiker

I was driving down Beverly Boulevard in a gold 1971 Volvo that looked like a spaceship. My dad had purchased the car for me a year before from a disillusioned actress in the San Fernando Valley. When we arrived at her home to pick up the car, the actress let us in and began sobbing. She said she was moving to Mexico, away from all “this,” waving dramatically out the window to the valley below. My dad turned her vulnerability into an opportunity to haggle her down to an unreasonable price, and now I was benefiting from the woman’s shattered dreams, on my way to Virgil Frye’s home in the Hollywood Hills to take an acting class.

Virgil was an actor, former golden gloves boxing champion, and father of Soleil Moon Frye. He had an entire room in his home stuffed from floor to ceiling with plastic dolls of Soleil’s character Punky Brewster, from her hit ’80s TV show. Virgil was in his 60s and longtime friends with Dennis Hopper. He told me I had the secret of acting, which was “just enough craziness.”

Olga Stein

The Scotiabank Giller Prize: How Canadian. Excerpt from the Introduction by Olga Stein

But regardless of whether or not the Giller declares an interest in ideas of nation when selecting juries, the prize does present a vision of Canadian literature. The visibility of a select group of works chosen by an awards jury contributes to constructing the contemporary national literature for the reading public.

— Gillian Roberts, Prizing Literature: The Celebration and Circulation of National Culture

Whether one agrees or disagrees with their mandates, loves or intensely dislikes the hype, glitz, and marketing surrounding them, literary prizes are here to stay. Like every other country, Canada is home to numerous literary awards, with the Griffin and Scotiabank-Giller prizes being perhaps our ‘biggest’ — the most spectacular, most followed and discussed. My own position is that literary culture needs prizes, and that the institutions that run literary prizes, despite the flaws we might attribute to them, perform an important public service.

My conviction derives in part from having been involved with the Books in Canada First Novel Award. That opportunity to contribute and learn about the administration of a literary prize was invaluable. Yet despite gaining an insider’s perspective on how literary awards are managed, and the privilege of observing first hand the joyful reactions of writers and publishers, I never arrived at a full appreciation of the cultural roles of literary prizes and their long-term and wide-reaching effects. Managing an award is not the same as studying it or thinking about it in ways that are dispassionate and informed by other types of scholarly understanding and research. My sense now is that prizes have grown more, not less important, especially as book reviewing in newspapers and respected literary journals has declined. This means that we need to understand their impact — good and bad — on literary culture in Canada. We need to conceptualize the kinds of practice/s prizes engage in, and grapple with the prizes themselves as institutions with specific kinds of cultural goals and corresponding influence.

Literary Spotlight with Sue Burge Will Return Next Issue

Books and Reviews. Edited by Geraldine Sinyuy

Books for Your Christmas Lists!

Gordon Phinn

Words Ignoring Wars

Books Referenced:

Agent of Change, Huda Mukbil (McGill/Queens 2023)

Tabula Rasa, John McFee (Farrar, Straus &Giroux 2023)

Paper Trails, Roy MacGregor (Random House Canada 2023)

Notes on a Writer’s Life, David Adams Richards (Pottersfield Press 2023)

The Last News Vendor, Michael Mirolla (Quattro Books 2019)

Maze, Hugh Thomas (Invisible Publishing 2019)

Jangle Straw, Hugh Thomas (Turret House 2023)

CellSea, Sasha Archer (Timglaset Editions 2023)

Broken Glosa, Stephen Bett (Chax Press 2023)

All the Eyes That I Have Opened, Franca Mancinelli (Black Square Editions 2023)

The Last Book of Madrigals, Phillipe Jaccottet, (Seagull Books 2022)

Mirror For You, Elias Petropoulos (Cycladic Press, 2023)

Fox Haunts, Penn Kemp (Quattro, 2018)

Poem For Peace, Penn Kemp & Others (Pendas Productions 2002)

Sarasavati Scapes, Penn Kemp & Others (Pendas Productions)

Incrementally, Penn Kemp (Hem Press Books 2023)

*

Memoirs make up a substantial part of every book season, and as we have noted, this boy’s interest level never seems to diminish. I am fascinated by the wide swath they cut in our ever increasingly diverse culture. Memoirists, historically, have shown a tendency to ego-based untrustworthiness, their exaggerations and untruths taking years to be exposed and corrected by diligent biographers. Meanwhile we read between the lines and learn what we can in the various pockets of society slumbering beneath that convenient category ‘subculture’. Memoirs by former CIA, FBI and MI5 personnel are not unusual, but CSIS, now that is rare. Huda Mukbil’s Agent of Change seeks to remedy that. Emerging with her life intact from the bloody turmoil of Ethiopia and Somalia in the 70’s to the relative calm of Egypt and then safe haven of Canada, this ambitious young woman seeks and then secures employment with the security services. Her experience is something of a double-edged sword, her conservative Muslim attitude and dress casting a shadow on her undoubted usefulness as a multi-lingual investigator in the era of Islamic Jihad and Isis affiliated terrorists groups and randomly inspired individuals.

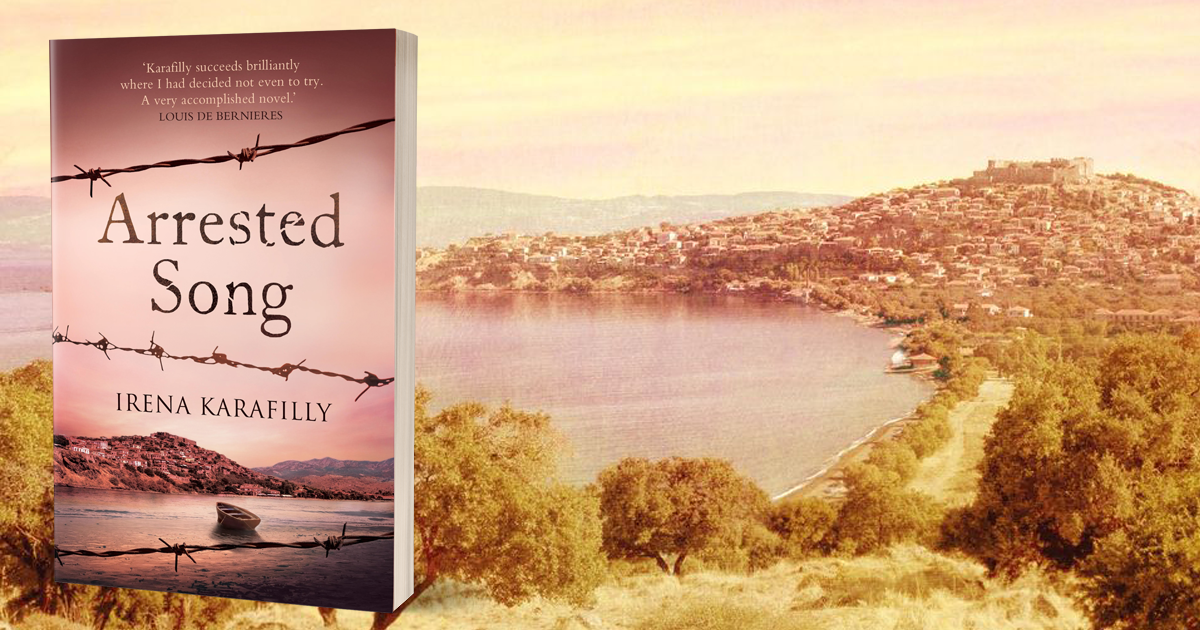

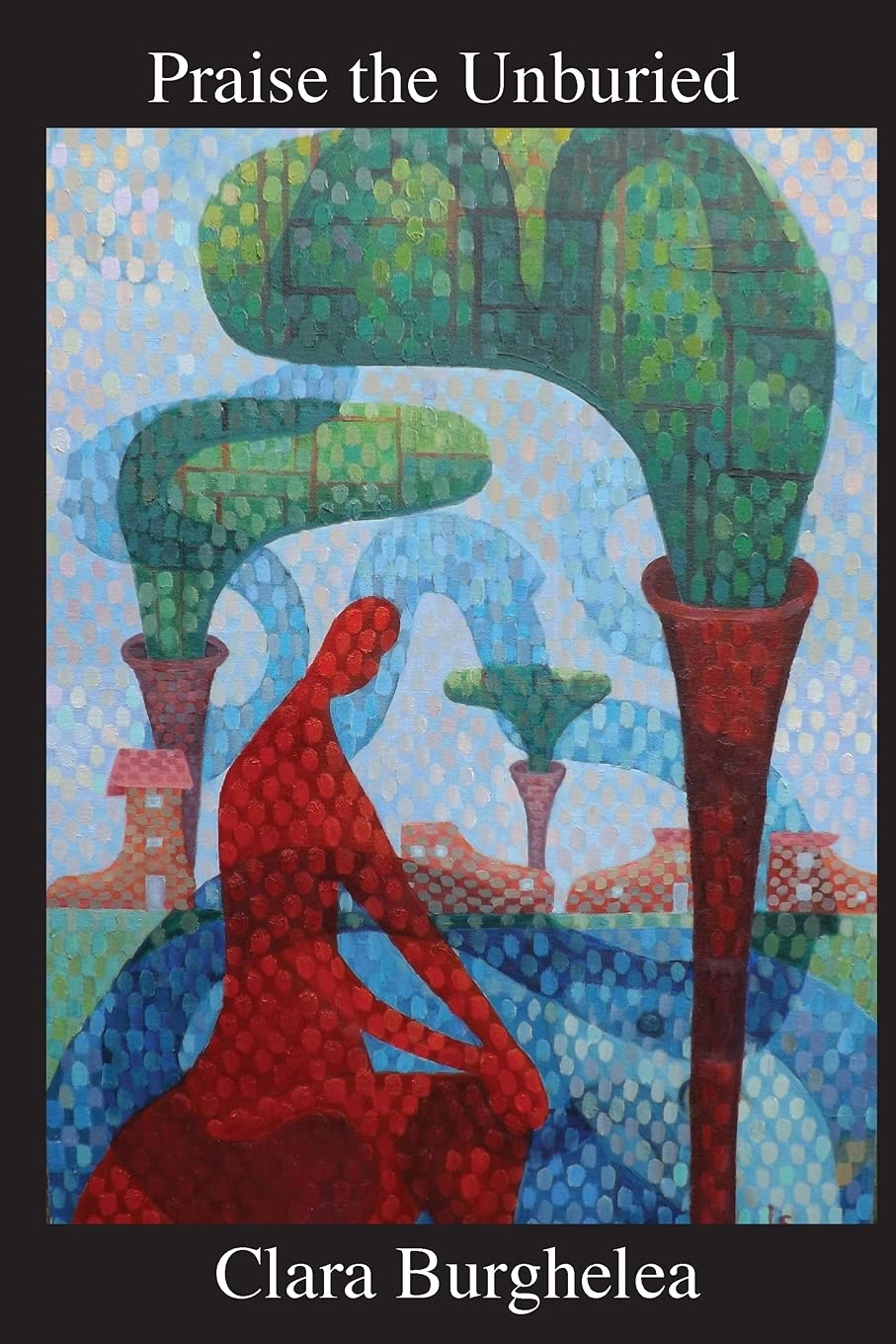

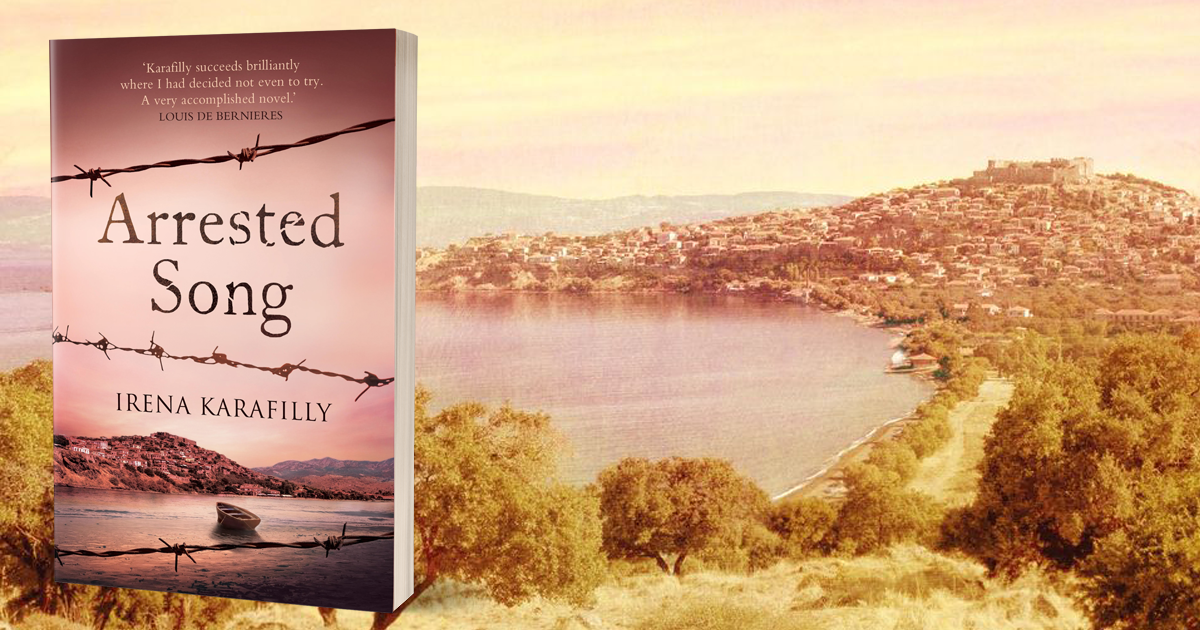

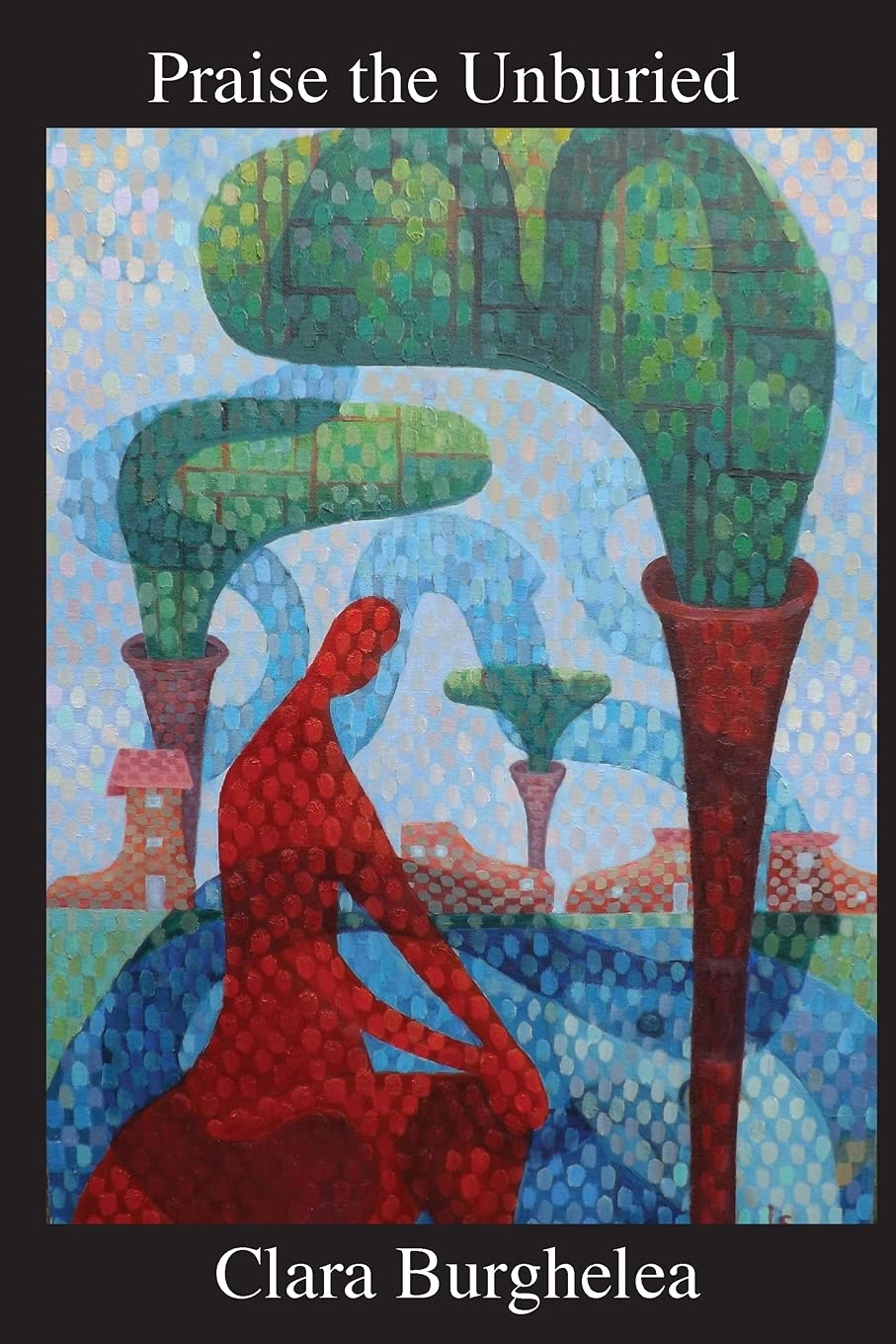

Diana Manole Reviews Clara Burghelea’s Praise the Unburied

Love and Bilingualism as Survival Strategies

Clara Burghelea, Praise the Unburied (Dublin: Chaffinch Press. 2021)

Praise the Unburied, Clara Burghelea’s second poetry collection, starts with the motto, “Every poem is the story of itself” (Tracy K. Smith), foreshadowing a metaliterary discourse. In a postmodern gesture, the poet indeed allows each poem to testify about itself, while also sharing several intermixed stories. In Greek mythology, King Midas cursed his ability to turn everything he touched into gold that gods bestowed upon him at his own request. In a much more constructive way, Burghelea has the talent to transform everyday life experiences into poetry and an homage to language and emotion. All poems not only have a rich vocabulary and surprising imagery, but also a hypnotic rhythm, which is worth noting, as English is the second language of the Romanian-born poet, residing in the U.S.

Every time she glances at the world, “At the back of your mind, a poem ready to stain the page.” Ordinary details from Romania, the United States, and Greece are consistently given poetic meaning, while the abstract is casually turned into matter, like in “pain lived in the zippered pocket / of my purse, ruffling its silver scales” (“I haven’t thought about my mother in months”). In contrast, humans with a “languaged body” are broken into little pieces, sometimes down to atoms, until their raw emotions are uncovered: “Pain is hunger, / its roots curling into the flesh. / Tune your ear to its fire. Simmer the tendrils” (“Prayer with Lullaby Eyes”). Burghelea’s love poems focus on the body as a literal open book, “A man reads braille on your ribs, fingertips / soaking in flesh” (“Impermanence”), or on close-ups of the romantic partner, “My ear finds your chest, / then the dip of your neck / where flakes of fleur de sel / inhabit my lips” (“Day’s Seams”). After the end of a relationship, the speaker struggles to “overcome co-dependence,” but coincidental sensory details make it impossible, “quick at semaphoring your presence / when the Starbucks kid rolls the r / in my name” (“Some Morning Unease”).

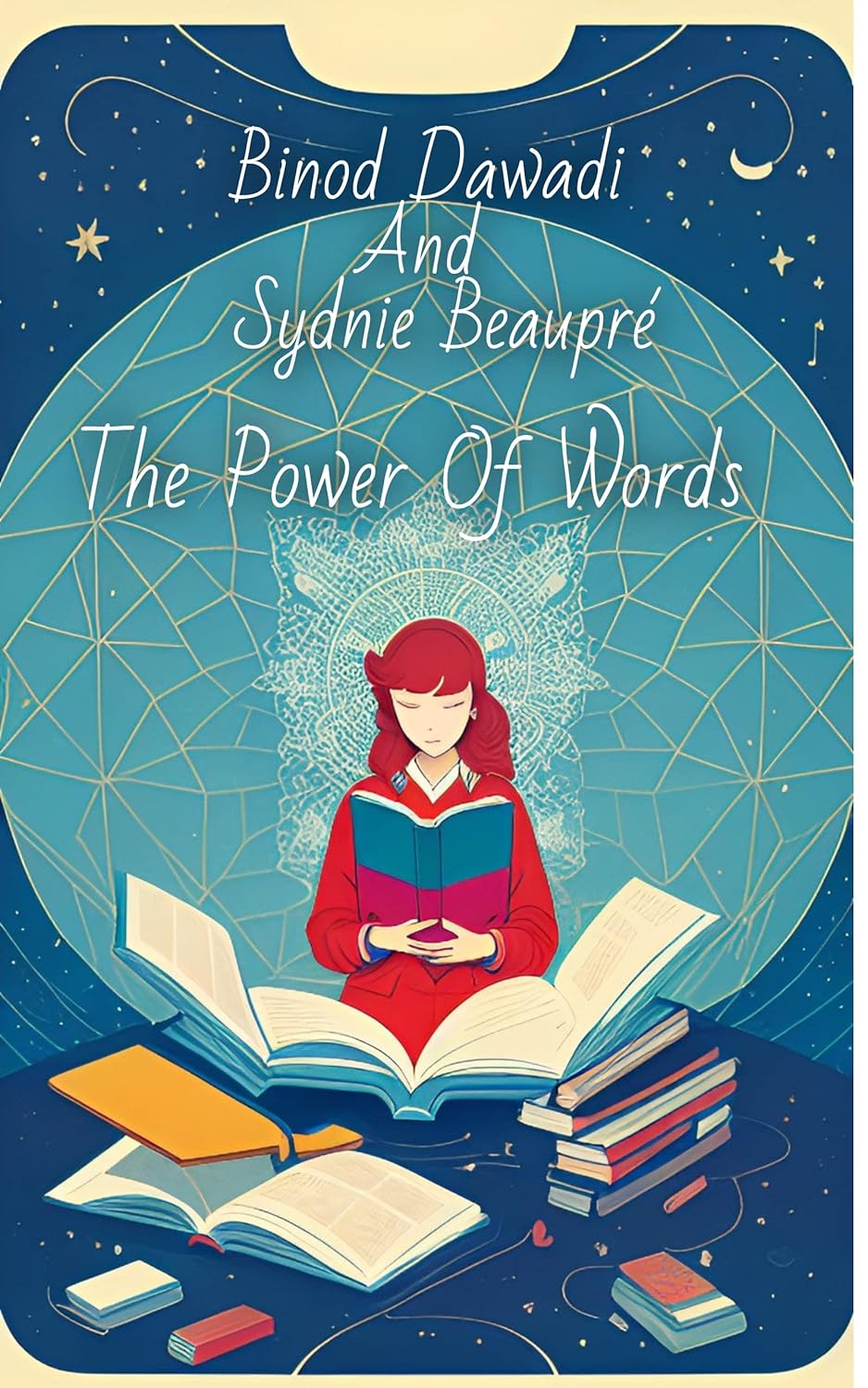

Sushant Thapa Reviews The Power of Words

Critical Beauty of Words: The Power of Words

I am thrilled to have read “The Power of Words,” a poetry collection written by Binod Dawadi from Nepal and Sydnie Beaupre from Canada who doubles as editor. This collaboration of two poetic souls has created indelible marks on the sands of modern literature.

But it can also destroy human beings,

By its anger,

This is because human beings are,

Making earth their puppet and playing with it. (Earth) ( 24)

The above-mentioned poem titled “Earth” is a critical tribute to the mother earth. In this collection, there is a poem on war which calls for peace. The poems in this collection are comfortable, beautiful, not difficult to understand and peaceful. Readers of any age can find this book graspable. The discrimination between race, caste and gender should be stopped and the book stands with this idea. There is a path of guidance which is illuminating in this collection. Very precise and nurtured words take us to a journey in this book. Life is one and everyone has a precious life. When a poem is mentioning about life, it feels as if a larger-than-life idea is present in the depth of the poem.

Dr Geraldine Sinyuy Reviews From Africa with Love

From Africa with Love: Voices from a Creative Continent curated and edited by Kelly Kaur in conjunction with Wole Adedoyin, Director, IHRAF African Secretariat. A Publication of the International Human Rights Arts Festival (IHRAF), 2023.

From Africa with Love: Voices from a Creative Continent is a collective call for revival, a revolution churned through all genres of creativity by emerging young African human rights activists. The throbbing of the heart of these committed African writers to see that the continent is entirely liberated from the shackles of all forms of human rights violation is like magma hitting the bowels of Mount Kilimanjaro. From Kenya to Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Ghana, Malawi and across the rest of Africa, the writers seem to sing the same song, a song of sorrow, a lamentation and a prayer for change to come soon.

Once you start reading the book from the first piece, your hair stands at its ends and goose pimples become part of you until you slam close the last page of the book. The first story in the anthology, “Dying to Audrey” by Abugyer Muse Stephani highlights the ordeal of a married career woman who has to give up her job as a bank worker in order to become a house wife when baby Doofan is born. As it often happens in Africa, Audrey’s mother-in-law having convinced the family that Audrey’s excessive demands are responsible for sending her son to the grave snatches her two children, Doofan and Terngu, 5 and 3 years old respectively.

Poetry. Edited by Clara Burghelea

Mykyta Ryzhykh

The sky is moving

The ant's gaze falls into the suggestion of life

Failure of life after adulthood

Older children are moving into the abyss

The abyss from which it all began

The iron tooth of a smile haunts the blind

The ash sketch of a heart beats like a real one

Who fell into whose life at that moment when a billion natural coincidences came together?

Gender, age, physical (etc...) contingencies of thought over the abyss of existence

Examination of immediacy, a patch of eyes, a rush of touch

And overhead the sky is in continuous motion

Yuan Hongri

Never-withering Light

I can’t say the mystery of the gods yet,

the devil is coveting the diamond of heaven.

There is a golden kingdom whose light is like wine inside the ancient earth.

The smiles of the gods are beside you,

as if they are the rounds of invisible sun and moon.

And your soul is ancient and holy

twinkle with the never-withering light of stars.

不凋谢的光芒

我还不能说出那诸神的奥秘

魔王在觊觎天国的钻石

在这古老的大地的体内

有那光芒如酒的金色王国

诸神的笑容就在你身旁

仿佛一轮轮隐形的日月

而你的灵魂也古老神圣

闪烁辰星那不凋谢的光芒

Charlotte Amelia Poe

in this corner of the universe there is a constellation set aside for you

If you buy enough gold acrylic paint, and paint stars on your ceiling against the dark, then maybe, just maybe, the world won’t end.

And if it ends anyway, debris beating at the plasterboard as the ceiling groans and the stars start to crack and splinter, then god, at least you’ll have something to look at, to be less alone as home swallows you whole.

Gordon Phinn

For Charles Simic

Yes, you were here, for what

Now seems an unquantifyable idyll

In that picnic of horrors

Holding forth in the headlines.

Only now do I see that trail of

Breadcrumbs, artfully arranged

To tempt the idle into exploring

The maze of your curiosity.

Arriving at a semblance of center

One sees the all too predictable

Mirror, making an elegant mockery

Of the verse lovers' vanity, as the

Smile of the Buddha creeps up from

Behind, waiting to dislodge the

Sorrow and the pity.

Mansour Noorbakhsh

To the extent of all your surroundings

__Dedicated to all working children.

“It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.” __Frederick Douglass

Maybe you have been sitting for hours behind trees or in the shade of rocks and hills waiting for the train to come.

Maybe you are bored of waiting. Maybe you are disappointed. Maybe you have gone to the point of changing your decision and going back. When the afternoon heat has you drenched in sweat.

But the train has finally arrived. With his awesome noise like a roaring monster. With its imposing body that shakes the ground and your whole body with every rotation of its wheels.

After all this waiting, now it’s time to scream in unison with the terrible sound of the train and not worry someone shouts angrily “Shut up”.

You can shake your hands and your whole body with all your heart, like a little demon next to a big demon, next to a train that roars and grinds its chest on the ground and moves forward.

Shake your whole body and shout as you run side by side, next to the roaring train. Raise your hands with clenched fists and scream at the top of your lungs power. Run with all your body. Show yourself to all the phenomena around you, so that you forget everything, even the demon of the train.

All this doesn’t take more than a few minutes. Finally, the train passes there. You stop running and screaming. But what remains is a deep silence that casts a shadow over everything. It is as if everything has become silent in front of you with mixed respect and fear. Then you feel yourself more than before. You don’t scream anymore. You don’t run anymore. But you feel yourself, your body, though small, but you feel it as wide as all your surroundings. You are calm now, like a river that moves in a wide bank with a peaceful appearance. Your restlessness and worries are temporarily over. You slowly return with a broader sense of all the things around you. Now you walk slowly, but you still feel that the ground is shaking under your feet.

Although you are now breathing slowly, but still those unfinished screams jump out of your chest like scattered coughs unconsciously for a while. It’s as if the little monster is spitting out all his suppressed feelings of injustice, humiliation, and the suffering of working as a slave, running barefoot, and sleeping hungry.

And your hot and feverish cheeks have bloomed now, as if they have tasted a real lovely kiss.

Dominik Slusarczyk

The Peasant’s Prayer

Yesterday I prayed so

Today I sit on my sofa and

Wait for my prayers to come true.

Soon I will have

Someone to hug but

I won’t hug them in

Case I break them.

John Grey

THE BULLY IN THE TREE

In the fork of a tree,

stands the bully boy.

Gripping a branch in each hand,

he puffs out his chest proudly.

Even if you can’t see him

from where you are,

you’re surely familiar

with the broken window,

the kid with two black eyes,

sobbing on the doorstep.

And you’ve no doubt heard

of the money stolen

from a neighbor’s purse

And the cuss words

uttered loudly in the school room.

A gust of wind tries

but can’t blow him down.

Someone shakes the trunk

but that doesn’t move

him either.

But here comes

the kid with the two black eyes

and he’s clutching some kind

of hand saw.

His eyes brighten

as he thinks ahead.

Rachel J Fenton

Peas on Earth

Seedlings greetings, I write in chalk

on reusable labels, tuck them in the pots

recycled and covered with paper then we walk

to our neighbors. My son makes each stop,

running up the steep gardens to learn

kindness isn’t concrete, it must be grown.

Claudia Wysocky

Heaven and Hell

Silence fills the air,

as I sit, alone,

among endless rows of graves.

I wish for heartbeats,

for laughter,

for tears.

I miss the noise.

But I know that I can't have it.

I can hear the footsteps of the living,

but there's no sound for me.

Silence surrounds me,

as I lay in my own void,

a void of life,

eternal and silent.

I will never know happiness again.

But I accept it,

lying here, alone,

among endless rows of graves.

It was fun being dead for a while,

to feel the quiet

and the peace.

I thought hell would have fire and brimstone,

but I guess that's only what they tell us.

I'm moving on now,

accepting my reality.

And I know that one day,

I'll find my meaning,

In the cold abyss.

But for now, all I have is silence,

a silence that never ends.

And I bet there's fire in heaven.

Foolish Understanding

The things I thought unmeetable—unattainable—as if from Eden—

Forever luring us with what could never be pure in value as it might have been—

Or so we've all been told:

But why should my heart believe it this for so?

This is what I know!

My dreams!

As clear as the words of my own ears—

Unencumbered by notions of what I was or would be.

Just a child at that point in time;

Unaware of the traps or whims of foolish understanding.

Always trying, always striving.

And now, standing here--where was I standing before?

Ioana Cosma

Mother Earth

Pregnant is the earth and was from the beginning

its replenished womb bathes us all in light

it is forever birthing bringing forth offspring like

the sky once exploded to make room for life.

At times we hear its moans of labor, its trembling

voice from roaring falls, the naked skin of trees

that crack under the weight of time. A work of passion

of the earth who always forgives our childish crimes.

It is small and gigantic at once, not a star, but an

incandescent rock. Though it might feel like magic, her

creation is mostly an act of love superseding intelligent

design, the grace of artwork and man's climb up above.

We tread hurriedly and with no sympathy for its voluptuous

body that's nonetheless never vulgar even when it is raped

like the times when we scratch through its belly, suck on its

blood and cover its sumptuous breasts in concrete and glass.

Yet the earth remains pure waiting for the day when

its favorite children begin to see her devotion and selflessness

in the midst of the abundance of life that seems to have been

born for and through her, the smallest of gods.

R. Gerry Fabian

Seeking Asylum

What Freud jumble-juxtaposed?

Poor man. Forked helplessly

in great homo sapiens noodle soup.

(Chicken ego parlor play desire plus

sublimated id broth plus super ego

cemented noodle cocktail party

chatter.) Imagine telepathic

sensory flashes visualized

as cajun bayou needle voodoo.

A code vacuum scramble

shields interior exercise message.

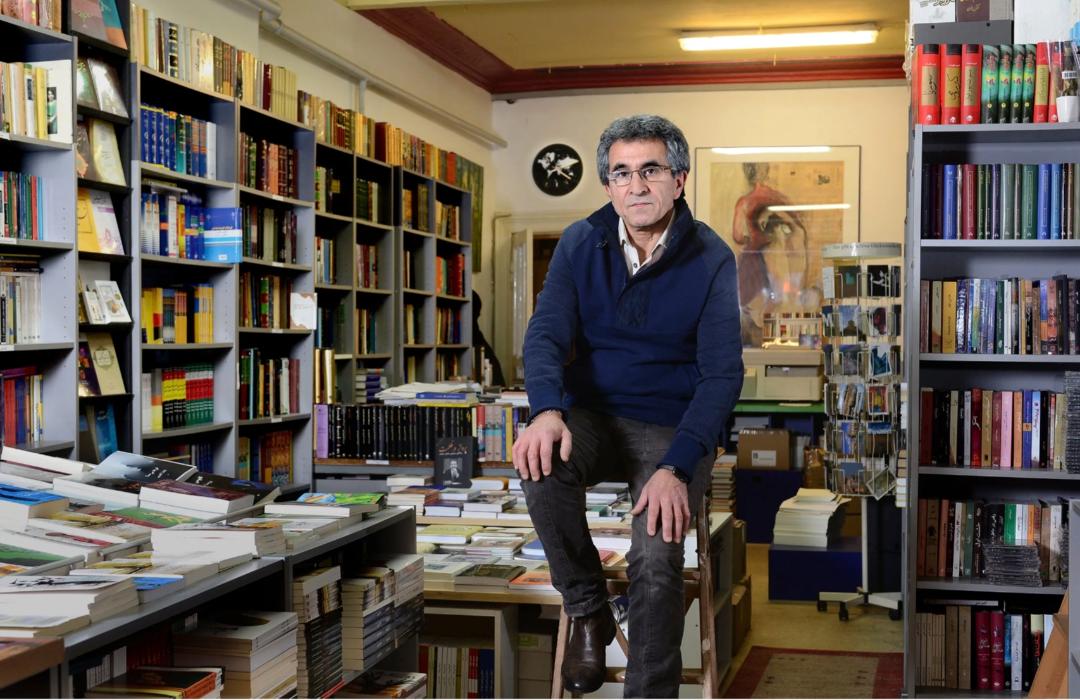

Abbas Maroufi

مردهها از مرگ نمیترسند

درد ندارند

رنج نمیکشند

تحقیر نمیشوند

کابوس نمیبینند

از جنگ نمیهراسند

به شکست نمیاندیشند

مردهها بازجو ندارند

تحت تعقیب نیستند

محاکمه نمیشوند

حساب پس نمیدهند

جهان را وا میگذارند

مردهها در کائنات میچرخند

تنها نمیمانند

با بال فرشتگان نوازش میشوند

احترام دارند

عشق من!

مردهها برهنه میخوابند

و من

هر شب

در آغوش گرم تو

میمیرم.

Every Night

The dead have no fear of death.

They have no pain

And do not suffer.

They are not humiliated

And have no nightmares.

They don’t dread war.

They don't dwell on defeat.

The dead have no interrogators.

They are not prosecuted

Nor are they investigated

Or held accountable.

The dead leave the world behind

And wander in the cosmos.

They are not left alone

Always caressed by angels’ wings

Always respected.

My Love!

The dead sleep naked

And every night

In your warm embrace

I die.